June 4, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

Should schools teach things that a lot of parents don’t like even if those things are true? If most parents are creationists, should the science curriculum nevertheless teach about evolution or mention that the earth is four billion years old rather than 10,000? Or should curriculum avoid anything that contradicts the views of parents?

When it comes to the facts that children are taught, Reihan Salam wants majority rule.

| And here the big challenge is whether or not you have public institutions that are advancing curricula and ideas that are basically going against freedom of conscience. Do we have situations in which people are being compelled to adhere to certain ideas, certain controversial ideas? |

(From his recent interview with Ezra Klein.)

I don’t know where Reihan went to school, but in the schools I went to you were “compelled” to learn what was taught. Well, you weren’t compelled. But you would do better on the exams if you did learn it. Even if your conscience told you that Aristotle’s four elements theory was spot on, your chem teacher went against your freedom of conscience and compelled you to learn about the periodic table. The exams didn’t have any questions about earth, air, fire, and water.

Reihan goes on:

| And I think that that’s something where it is good and healthy to have transparency in school curricula. I think it is good and legitimate to believe that parents should have access to good, reliable information about what is being taught and about the ideological content of what is being taught. This is obviously a very contentious issue, but I think that it goes part and parcel with our general belief and educational pluralism. That is the idea that schools tend to work best when they’re broadly aligned with the values and sensibilities of families. |

It sounds so good. Who could be against freedom of conscience, against transparency or good, reliable information, or pluralism, or families?

Of course, Reihan isn’t talking about creationism or phlogiston theory. He’s talking about Critical Race Theory, but the issue of who designs the curriculum is basically the same. What Reihan is offering is a calmer and more reasonable-sounding version of what louder right-wing politicians are saying. Much like the con man in “The Music Man,” they are telling the parents, “You got trouble my friends, with a capital T, and that rhymes with C and that stands for Critical Race Theory.” Twenty years ago, politicians like these were railing and legislating against “Sharia law,” which they claimed posed an imminent threat to freedom, family, and apple pie. Now it’s CRT. Plus ça change.

Should schools teach about the crucial place that race, especially the treatment of African Americans, has in American history and in the American present? It’s not a pleasant story, and it does not show White people as being predominantly noble. Not surprising that it makes some people feel uncomfortable or that they would prefer the “patriotic education” promoted by Donald Trump.

And if that’s what they want, in Reihan’s book that’s what they should have. He doesn’t say exactly what he means by “educational pluralism.” But it certainly suggests that “the values and sensibilities of families” should shape the curriculum. In many cases, that means that kids will get a Whitewashed version of US history, a version that does not make the majority feel uncomfortable.

But wait. Aren’t we past that? Don’t we acknowledge that slavery was bad and that the secession in order to preserve slavery was wrong? What about all those statues that have been torn down?

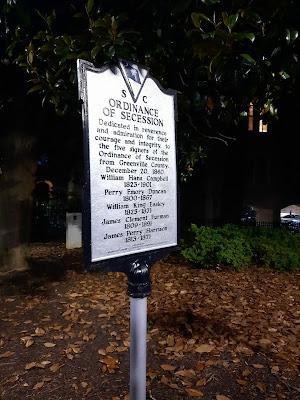

The same day that the Reihan Salam interview appeared, sociologist Peter Moskos tweeted a photo he had taken of a sign in Greenville, SC, a city of 70,000, 70% White, 23% Black. (The Greenville County population is 533,000, 76% White, 18% Black.) The sign was next to a statue of Robert E. Lee.

“Dedicated in reverence and admiration for their courage and integrity to the five signers Ordinance of Secession from Greenville County.”

Here’s the text Peter tweeted below the photo:

I really did not expect to see this. My naiveté. "In reverence and admiration"? These aren't founding fathers. These were literally traitors.

I don’t know what the history curriculum in the Greenville schools compels students to learn, but I would guess that, like the sign and statue, it is, as Reihan says, “broadly aligned with the values and sensibilities of families.” Well, the 70% of families that are White, not the 23% that are Black.