June 23, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Dan Myers, in a recent installment of

Blue Monster in Europe hears the band at Buckingham Palace play “Stayin’ Alive” and speculates, “The flag was up on the top of the palace, indicating that the Queen was home. I would like to think, therefore, that this performance was a personal request and that she was upstairs working on her own electric slide.”

I watched “The Queen” on DVD recently, which is how I know that the flag Dan refers to is not the Union Jack but the Royal Standard.

Here’s a clearer image.

It’s not the British flag, the Union Jack.

It’s difficult for us Americans to grasp the idea of monarchy. “Stupid” was the comment of the teenager-in-residence who was sitting a space or two down the couch from me as we watched the film.

But there’s something to be said for having a ceremonial head of state, someone who symbolizes the nation as a whole and who stands above partisan politics. The Queen is so far above politics that she’s not allowed to vote. We learn this early in the film, which opens with the election of Tony Blair as prime minister.

“The sheer joy of being partial,” says the Queen. As a person, she no doubt has her political preferences. But as the Queen, she must remain impartial. She is someone the entire country can look to as its leader.

Most European countries, with their long histories of monarchy, have retained a nonpolitical figure as symbolic ruler of the country. In some countries (England, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, etc.) it’s an actual monarch; in others, it’s a president, who has only ritual duties, while the actual business of running the country falls to the elected prime minister.

But in the US, we have this strange system where a partisan politician is also our ceremonial head of state. It is he who represents the country, attending state ceremonies, recognizing ambassadors, conferring honors, and carrying out other symbolic duties. In the minds of some citizens, to disrespect the president, therefore, is to disrespect the country, even if, as happened in 2000, that president got fewer votes than his opponent. How often have we heard that we must stand behind our president merely because he is our president?

To erode the good will that comes with this symbolic position, a president has to do a really bad job and over a fairly long time. It can be done (Mr. Bush’s latest ratings show only 26% of the country favorable, 65% unfavorable), but it takes sustained effort.

Giving the mantle of symbolic head of state to a partisan politician also can lead to the kind of arrogance we’ve come regretfully to expect of our presidents. They can come to think of themselves in near-kinglike terms — think of Lyndon Johnson’s famous remark, “I’m the only president you’ve got” — rather than as elected politicians. The Bush administration has taken this arrogation of power further than any of its predecessors, with their belief that they can

ignore laws they don’t like, withhold information from the Congress and the people, and use the justice system as a political tool.

There may be something about constitutional monarchies that curbs such arrogance. An early scene in “The Queen” shows Tony Blair coming to Buckingham Palace. He has just won the election in a landslide, but he will not be prime minister until he kneels before the Queen and

is officially requested by her to form a government. As historian Robert Lacey says in his commentary track on the DVD, “People feel it’s good that these politicians have to kneel to

somebody to be reminded that they are

our servants.”

In the US, the president is sworn in by the Chief Justice, the Supreme Court being the closest thing we have to an impartial power. But the justices are appointed by politically elected presidents, and as recent history has shown, the Court is quite capable of pure political partiality. Does anyone really believe that the vote in

Bush v. Gore was about the law and not about politics? All those five votes that in effect gave Bush the election were Republican appointees. The two Democratic appointees sided with Gore.

Nobody, not presidents or prime ministers, appoints the Queen. Moreover, as historian Lacey notes, the prime minister has to meet with the Queen every week and report to her. The US president does not have to report to anyone. Cabinet members and other administration officials may testify before Congress, and the president himself may hold press conferences. But as the current incumbent has demonstrated, it’s possible to greatly limit the amount of such questioning.

The only thing the US has that takes on some of the magisterial symbolism of the Queen is the flag, which, as an inanimate piece of cloth, cannot do all the things the Queen does.

Less officially — only somewhat less officially— there’s God. But over the last half century or so, the Republicans have successfully claimed both God and the flag as belonging exclusively to their party.

As “The Queen” unfolded, the more I watched this very human figure sorting our her roles as grandmother, mother, ex-mother-in-law, and Queen of England, the more I thought that perhaps monarchy isn’t such a bad idea.

(Hat tip and deep bow to Philip Slater, who blogged along similar lines to this post for his Fourth of July essay at Huffington Post.)

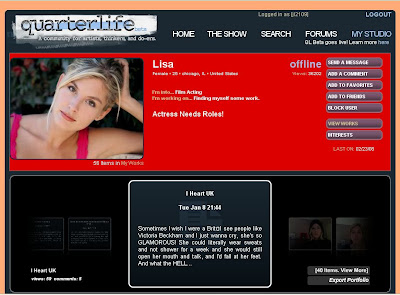

More interestingly, you can also see vlog entries from fans that are indistinguishable from the fictional vlogs. You can read the blog entries of the characters, and apparently you can send them a message, “add to friends,” etc. I haven’t tried it. I haven’t been able to get into writing to fictional characters since I stopped sending letters to Santa. But then again, I’m like so twentieth century.

More interestingly, you can also see vlog entries from fans that are indistinguishable from the fictional vlogs. You can read the blog entries of the characters, and apparently you can send them a message, “add to friends,” etc. I haven’t tried it. I haven’t been able to get into writing to fictional characters since I stopped sending letters to Santa. But then again, I’m like so twentieth century.