March 15, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

Namerology, the former Baby Name Voyager (here),is a great resource for anyone interested in graphs showing trends in baby names in the US. It uses the data from the Social Security Administration, but it’s graphs are much better than those you can create on the SSA Website. For instance, it allows you to compare names.

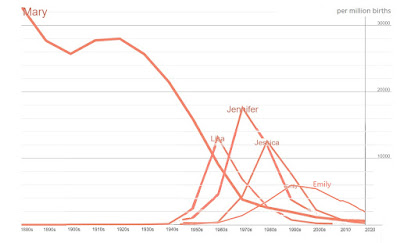

I wanted to explore the idea that the diversity of names is increasing. The most popular names today are not nearly as dominant as popular names in the past. It’s like TV shows. The ratings or share-of-audience of today’s most popular shows are numbers that twenty years ago would have marked them for cancellation. Compare the most popular name for girls born in the 1990s, Emily, with her counterpart in the 70s, Jennifer.

Jennifer’s peak was three times higher than Emily’s.

Jennifer also stacks up well against the top name of the sixties (Lisa) and of the eighties (Jessica).

Jennifer’s popularity was extraordinary. Jessica was at the top for nine of the eleven years from 1985 to 1995. And Lisa held top spot for eight years, 1962 - 1969. But Jennifer was number one for fifteen years, 1970-1984. We will probably never see her like again.

But then along comes Mary. The numbers for Mary back in the day dwarf those for Jennifer at the height of her popularity.

I read this graph to mean that the way we think about names has changed. Today, we just assume that you don’t want to give your kid the same name that everyone else has. You want something that different, but not too different. But a hundred years ago, distinctiveness was not important criterion for parents choosing a name. Year in year out, the girls name most often chosen was the same year in year out — Mary.

Names may be only part of a more general change in ides about children. Demographer Philip Cohen (here) speculates that compared with parents in the early 1900s, parents in the latter half of the twentieth-century saw each child as a unique individual. After all, children were becoming scarcer. From 1880 to 1940, the average number of children per family declined from 4.2 to 2.2, And while Mary remained the most popular name throughout that period, its market share declined from over 30,000 per million to about 20,000 per million.

The real shift starts in the 1960s. It may have been part of the general rejection of old cultural ways. But this was also the end of the baby boom. With new birth-control (the pill), having children became more a matter of choice. Family size declined even further. Each child was special and was deserving of a special name.