March 30, 2021

Posted by Jay Livingston

It’s nice to have your perceptions ratified so that you can stop asking yourself, “Is it just me that’s noticing this?” Lately, it seemed that I was hearing more talk about trauma — and for some things that didn’t seem especially traumatic. Katy Waldman heard the same thing. “Around every corner, trauma, like the unwanted prize at the bottom of a cereal box. The trauma of puberty, of difference, of academia, of women’s clothing.” Women’s clothing? Oh well, Waldman is a staff writer at The New Yorker and presumably more plugged in to the zeitgeist than I am. That sentence is from her article “The Rise of Therapy-Speak” (here).

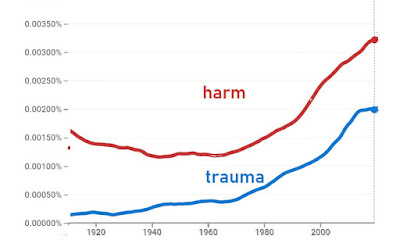

Google nGrams confirms our suspicions. Mentions of both trauma and harm rose starting about 1970.

But trauma’s market share increased.

The important difference is that while both trauma and harm injure a person, trauma implies long-lasting psychological damage.

Waldman can’t decide whether therapy-speak is really a recent development. The title of the article (“The Rise of . . .”) implies that it is, and she says that “the language of mental health is burgeoning.” But she also quotes a psychologist who tells her that “the language of the therapist’s office has long flooded popular culture.” I agree. The specific words that are in fashion come and go — trauma is on the rise, inferiority complex and midlife crisis are relics of the past — but the process remains the same. So does the criticism. Waldman takes aim at “therapy-speak”; forty years ago the same target was “psychobabble.”

Psychotherapeutic discourse usually remains inside the gated city of the educated liberal elite. I imagine that on Fox News there’s about as much talk of “toxic” relationships or emotional “triggers” as there is of “mindfulness.” Those outside this world can find therapy-speak and its attendant world-view annoying. Waldman speaks of “irritation that therapy-speak occasionally provokes,”

| the words suggest a sort of woke posturing, a theatrical deference to norms of kindness, and they also show how the language of suffering often finds its way into the mouths of those who suffer least. |

Therapy-speakers are annoying partly because they are parading their self-absorption. As Lee Rainwater said a half-century ago, “the soul-searching of middle class adolescents and adults,” when compared with the problems of the poor, “seems like a kind of conspicuous consumption of psychic riches.” Nobody likes a show-off.

In one important way, trauma talk is different from earlier therapy-speak. Among the people Waldman is writing about and their counterparts in earlier generations (those who suffer least), therapists, neuroses, depression, anxieties, etc. have long been part of the conversation, These are, after all, the people who went to Woody Allen films. The trauma frame shifts the focus to some external source. To some extent that has always been true of psychoanalytic ideas, with their emphasis on childhood experiences with parents. But calling it trauma puts it in the same bin as the post-traumatic stress disorder suffered by soldiers who have been in combat. Besides magnifying the harm of these more mundane forms of suffering, it also implies that the harm was done by others, whether by intent or inadvertently. It’s as though Philip Larkin had written, “They traumatize you, your mum and dad.”

-----------------

* “Therapy-speak” might be Waldman’s own coinage. An Internet search turned up only one instance of this term, in a 2019 article at Slate.