September 21, 2024

Posted by Jay Livingston

“Two pair wahr,” said the young woman next to me in the Place Aristide Briand in Carpentras. We were both there for the marché aux truffes, a truffle market held every Friday morning in the cold months. The waitress at the restaurant Thursday night had told me about it, so Friday morning I was up early to make the half-hour drive. I was early. A few dozen people were standing in a loose circle. The farmers, with their baskets of truffles and their hand-held balance scales, stood in the center. At 8:45, someone blew a whistle and trading started.

I had come just to see the market and take some photos, but I started talking with a couple of young women standing near me, and after a few minutes they were helping me buy a half kilo of truffles. I told them that I wanted to take them back to my friend in Paris, but I didn’t think it was a good idea to keep them for several days in the paper bag I was now holding.

They told me that I should go to the grocery store and get some rice, then to the droguerie (housewares store) and get “two pair wahr.” My so-so French had been adequate to the task so far, but here was a French word I did not understand. “Two pair wahr,” she repeated, and mimed prying a lid off a container.

Tupperware. Of course. You put the truffles in and fill it with rice. It won’t smell up the car, and when you do get back to Paris, whatever dish you decide to use the truffles in,, you’ll also have the best tasting rice you’ve ever had,

It was the only piece of Tupperware I ever bought.

Last week, Tupperware filed for bankruptcy.

A blog by Jay Livingston -- what I've been thinking, reading, seeing, or doing. Although I am an emeritus member of the Montclair State University department of sociology, this blog has no official connection to Montclair State University. “Montclair State University does not endorse the views or opinions expressed therein. The content provided is that of the author and does not express the view of Montclair State University.”

The Party's Over

Jeopardy III: Losing Their Religion. Again.

July 1, 2023

Posted by Jay Livingston

I didn’t see this when it happened nearly three weeks ago. None of the three Jeopardy contestants knew “hallowed be thy name.”

Nor, until now, was I aware of the distress and outrage it provoked.

For me, it was déja vu.

I was on Jeopardy fifty years ago. At the studio, before the taping began, they had some of the contestants do a practice round. Presumably, this was to help us feel comfortable with the cameras and lights and other aspects of the set. I was not one of those selected, so I sat nearby and watched. One of the categories on the board was The Bible.

“OK, let’s go,” came the voice from the control room. They ran through a few questions, and then a contestant, after answering a question correctly, asked for The Bible.

The plate with “$10"* on it slid up revealing the question which the host then read: “In the Book of Matthew, he says, ‘Suffer the little children to come unto me.”

Silence. Nobody rang in. Then over the speakers came the deep voice from the control room: “They don’t come any easier in this category, people.”

---------------

* Yes, $10. The dollar values of questions then were 1/20 what they are now. For more on my Jeopardy appearances, see these earlier posts.

Not Ken Jennings, But . . .

Jeopardy II: Audiences — à la Goffman and ABC-TV

To Serve and Protect and Empathize

May 3, 2023

Posted by Jay Livingston

A friend of mine here in New York was the victim of a property crime, a larceny. The bad guys had broken into his car and taken whatever wasn’t locked down, mostly books as I recall (this happened a long time ago). He went to the local precinct to report it. Eventually the desk sergeant acknowledged his presence. “Somebody broke into my car and took all my stuff.”

“So what do you want me to do about it?” said the sergeant.

The officer’s response is understandable and quite reasonable. There’s no way the thief could be caught or the property recovered. Besides, this type of crime happened frequently. To fill out the paperwork or do anything would just be a waste of police time. My friend knew all this, but he was still not happy about the way the cops treated his victimization.

I remembered this anecdote when I saw some data from Portland showing low levels of satisfaction with a crime reporting system there. It also reminded me of the previous post about satisfaction with responses to medical questions. When people seek immediate medical advice online, they are more satisfied with the responses of a non-human (ChatGPT) than with those of a doctor. Doctors were five times more likely to get low ratings for both the quality of the information and the empathy conveyed. Three-fourths of their responses were rated low on empathy.

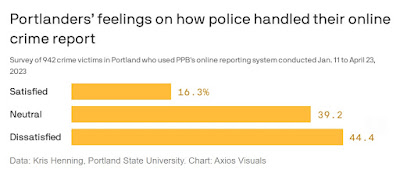

Something similar could be happening when people are victims of crime. In Portland, as in many cities, victims of non-violent crimes can use the online reporting system rather than calling the cops. Most people find the system easy to use, and it frees police resources for other matters, but so far it’s not getting high marks. Only 16% of those who used it said they were “Satisfied” and nearly three times that many said they were “Dissatisfied.”

Could ChatGPT help? As with medical reporting, the crucial factor is whether the police seem to care about the case. People who received a call or email from the police in response to their online report were twice as likely to be satisfied, even though the callback sometimes came weeks after the victim had filed the report and even though many of the victims or property crime merely want a case number for insurance purposes.

ChatGPT or some similar program could send this kind of email and respond to questions the victim might have. I’m not sure what ChatGPT’s initial message would sound like, but it wouldn’t be, “So what do you want me to do about it?” Putting ChatGPT on the case wouldn’t have any effect on the crime rate or the clearance rate, but it might make a difference in how people thought about their local police.

Your GP or ChatGPT

May 1, 2023

Posted by Jay Livingston

| Help. A couple of hours ago, I swallowed a wooden toothpick that the cook had missed when removing them from the stew he’d made. It wasn’t that long, an inch or so, and it couldn’t have been very sharp since I didn’t feel it much when I swallowed it. But can it be serious or even fatal? |

A question similar to this was posted on Reddit’s r/AskDocs forum, where doctors or other healthcare professionals post answers. Here are two responses.

| If you’ve surpassed 2-6 h, chances are they’ve passed into your intestines. Which means it can’t be retrieved easily.

Many people can swallow razorblades and toothpicks without issue. In case you develop stomach ache, then don’t hesitate seeking out an emergency room, and remember to point out the swallowed tooth pick. For now, they won’t be doing much. |

| It’s natural to be concerned if you have ingested a foreign object, but in this case, it is highly unlikely that the toothpick you swallowed will cause you any serious harm.

Toothpicks are made of wood, which is not toxic and will not cause poisoning. However, it is possible for a toothpick to cause injury if it becomes stuck in the throat or if it punctures the digestive tract. However, this is unlikely to happen with a dull, cooked toothpick that is only 2 cm long. If you are experiencing any discomfort or symptoms such as abdominal pain, difficulty swallowing, or vomiting, it is important to contact a health care provider for further evaluation. However, if you are not experiencing any symptoms, it is safe assume that the toothpick has passed through your digestive system and you do not need to concerned. It’s always a good idea to be cautious when consuming food and to remove any foreign objects before eating. It's understandable that you may be feeling paranoid, but try not to worry too much. It is highly unlikely that the toothpick will cause you any serious harm. |

How would you rate the quality of each response on a 5-point Likert scale (very poor, poor, acceptable, good, or very good)?

How would you rate the empathy or “bedside manner” of each response (not empathetic, slightly empathetic, moderately empathetic, empathetic, and very empathetic)?

The first response is from an actual doctor. The second is from ChatGPT. Which did you rate more highly?

Chances are that your evaluation was no different from those of a team of three licensed healthcare professionals who reviewed 200 sets of questions and answers. On measures of both quality and empathy, ChatGPT won hands down. (The JAMA article reporting these findings is here.)

On a five-point scale of overall quality, the ChatGPT average was 4.13, Doctors 3.26. (On the graph below, I have multiplied these by 10 so that all the results fit on the same axis.) On both Quality and Empathy, Doctors got far more low (1-2) ratings (very poor, poor; not empathetic, slightly empathetic), far fewer high (4-5) ratings.

People who ask medical questions are worried. If you have something going on with your body that seems wrong, and you don’t know what it is, you probably are going to have some anxiety about it. So ChatGPT might begin with a general statement (“It’s always best to err on the side of caution when it comes to head injuries,” “It’s not normal to have persistent pain, swelling, and bleeding. . . “) or an expression of concern (“I’m sorry to hear that you got bleach splashed in your eye”). The doctors generally focused on the symptom, its causes and treatment.

Doctor responses were considerably more brief than those of ChatGPT (on average, 50 words compared with 200). That’s partly because of time. If doctors were at all concerned with an efficient use of their time, they couldn’t turn out the longer responses that ChatGPT generated in a few seconds.

But I think there’s something else. For patients, the symptom is new and unusual. They feel worried and anxious because they don’t know what it is. But the doctor has seen it a thousand times. It’s routine, not the sort of thing that requires a lot of thought. Here’s the diagnosis, here’s the recommended treatment, and maybe here are some other options. Next.