May 19, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

“Dr. Oz should declare victory. It makes it much harder for them to cheat with the ballots they ‘just happened to find.’” So posted Donald Trump on his social media platform Truth Social.*

He may be right. By declaring victory, you make that the default outcome. You put the burden of proof on the other side. That was Trump’s strategy in 2020. He started claiming victory before the election. Thus, his claims of victory after the election were merely a continuation of an established “fact,” even though that fact was established only by Trump’s repeatedly asserting it. That made it easier for his supporters to remain convinced that he won and to believe all his claims about fraudulent vote counts. It also apparently has raised doubts even among those who were not ardent Trump supporters.

In the pre-Trump era, a candidate in Dr. Oz’s position would say something like, “Well, it’s a very close, and we’ll have to wait for all the absentee ballots. But when all the votes are counted, I’m sure that we will have won.” That is in fact the situation that exists.

Or he could play the Trump card and declare victory – loudly and frequently, on TV and on Twitter. If the final tally shows McCormick winning, that result will seem to go against an established fact. And even if courts and recounts uphold the result, Dr. Oz will avoid being labeled a loser.

Maybe this same strategy would work in other areas. I imagine Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks, declaring on Tuesday that a Mavericks victory the next night was certain. Then, after the game, which Golden State won 112-87, he could claim that there was basket fraud – that many of the Warriors’ points were “fake baskets.” He could get Dinesh D’Souza to make a film showing nothing but Mavericks’ baskets and the Warriors’ misses. He could call up the scorekeeper and tell him to “find me just 26 more points.”

OK, maybe we’re not there yet in basketball. But in politics this is another area where Donald Trump may have a lasting influence. I expect that more politicians will use the strategy of declaring victory and then claiming voter fraud. The gracious concession speech will become a rare event.

----------------------

* I think that they call these posts “truths.” Twitter has Tweets; Truth Social has Truths. I don’t think they have yet come up with a verb equivalent to Tweeting. “Dr. Oz should declare victory,” Donald Trump truthed?

A blog by Jay Livingston -- what I've been thinking, reading, seeing, or doing. Although I am an emeritus member of the Montclair State University department of sociology, this blog has no official connection to Montclair State University. “Montclair State University does not endorse the views or opinions expressed therein. The content provided is that of the author and does not express the view of Montclair State University.”

Making “I Won” the Default

“Julia” — Serving Up Words Before Their Time

May 4, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

“The Marvelous Mrs. Anachronism” (here) is the post in this blog with by far the most hits and comments. And now we have “Julia,” the HBO series about Julia Child and the creation of her TV show “The French Chef.” It’s set in roughly the same time period, the early 1960s. And like “Mrs. Maisel,” it offers a rich tasting menu of anachronisms.

I don’t know why the producers don’t bother to check their scripts with someone who was around in 1962 – a retired sociologist, say, who is sensitive to language – but they don’t. Had they done so, they would have avoided the linguistic equivalent of a digital microwave in the kitchen and a Prius in the driveway. They would not have had a character say, “I’m o.k. with it.” Nor would an assistant assigned a task say, “I’m on it.” Nobody working with Julia would be excited to be on the front lines of “your process.” “Your method” perhaps or “your approach” or even “all that you do,” but not “your process.”

If you’re a TV writer, even an older writer of fifty or so, these phrases have been around for as long as you can remember, so maybe you assume they’ve always been part of the language.

But they haven’t. Sixty years ago, people might have asked how some enterprise made money or at least made ends meet. But they would not have asked it the way Julia’s father asks her: “What's the business model down there? Does public television even* have a business model?”

In her equally anachronistic reply, Julia says, “Nothing's a done deal yet,” That one too sounded wrong. I don’t recall any done deals in 1962.

To check my memory, I went to Google nGrams. It shows the frequency of words and phrases as they occur in books. Most of the phrases that seemed off to my ear did not appear in books until the 1980s. A corpus of the language as spoken would have been better, and there’s a lag of a few years before new usages on the street make it to the printed page. But that lag time is certainly not the twenty years that nGrams finds.

In another episode, we hear “cut to the chase,” but it was not till the 80s that we skipped over less important details by cutting to the chase. (Oh well, at least nobody on “Julia” abbreviated a narrative with “yada yada.”) Or again, a producer considering the possibilities of selling the show to other stations says, “This could be game changer.” But “game changer” didn’t show up in books until four decades after “The French Chef” went on the air.

“This little plot is genius,” says Julia’s husband. It may have been, but in 1962, genius was not an adjective. An unusual solution to a problem might be ingenious, but it was not simply “genius.” Even more incongruous was Julia’s telling the crowd that shows up for a book signing in San Francisco, “I'm absolutely gobsmacked by this turnout.” Gobsmacked originated in Britain, but even in her years abroad, Julia would not have heard the term. Brits weren’t gobsmacked until the late 1970s, with Americans joining the chorus a decade or so later.

I heard other dubious terms that I did not know how to check. “The Yankees are toast,” says one character, presumably a Red Sox fan. It’s not just that in 1962 the Yankees were anything but toast, winning the AL pennant and the World Series; I doubt that anyone was “toast” sixty years ago.

The one that bothered me most was what Julia’s friend Avis says after making a small play on words. She adds, “See what I did?” I’m pretty sure this is a very recent usage and was not around in 1962. I’d just as soon not have it around today.

Finally, in the latest episode, which I just now saw and which inspired me to write this post, we have the anachronism that nobody notices — “need to” instead of “should” or “ought to” or other words that carry a hint of what is right or even moral. In “Julia,” a young couple meet for lunch at a diner. It’s a blind date, and as they talk, it becomes clear that they are a good match. They talk some more, and we cut to a different plot line. When we come back to the diner, the couple are still there, still talking, but they are now the only ones left in the place. The waitress comes to the table and tells them patiently, “You need to go.”

What she means of course is that she needs for them to go. In 1962, she would not have phrased it in terms of their needs. She would have said, “You have to go.”

-------------------------------

* “Even” as an intensifier in this way may also not have come into use until much later in the century. See this Language Log post on “What does that even mean?”

Robert Morse, 1931 - 2022

April 21, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

The opening sentence of the Times obit for Robert Morse mentions his roles in both “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” in 1961 and “Mad Men” forty-six years later. Those Morse roles were linked in subtler ways — the characters’ career trajectories and their clothing choices, as. I pointed out in a 2010 post which I am hauling out of the archives on this Throwback Thursday.

The post was mostly about America’s concern with “conformity,” but Morse’s performance in the video from “How to Succeed” is worth two minutes and fifty-three seconds of your time even if you’re not considering the cultural-historic questions.

*******************

July 1, 2010Posted by Jay Livingston

“How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” was on TMC Tuesday night in honor of the centenary of Frank Loesser’s birth. The Broadway show opened in 1961, sort of a musical comedy version of William H. Whyte’s 1956 best-seller The Organization Man.

Loesser’s musical was light satire; Whyte’s book was sociology. But the message of both was that corporations were places that demanded nearly mindless conformity of all employees. Or as Mr. Twimble tells the ambitious newcomer (J. Pierpont Finch), “play it the company way.”

FINCH:When they want brilliant thinking / From employeesConformity was a topic of much concern in America in those days, in the popular media and in social science (as in the Asch line length experiments). Today, not so much.

TWIMBLE: That is no concern of mine.

FINCH: Suppose a man of genius / Makes suggestions.

TWIMBLE: Watch that genius get suggested to resign.

the Organization Man, if he ever existed, is dead now. The well-rounded fellow who gets along with pretty much everyone and isn’t overly brilliant at anything sees his status trading near an all-time low. And all those brilliant screwballs whose fate Whyte bemoaned are sitting now on top of corporate America.

That’s one version. I don’t really know if the corporate climate is different today (where’s an OrgTheorist when you need one?). No doubt, “brilliant screwballs” can find save haven in corporations, at least in areas that require technical brilliance, and some may wind up at the top. But I wonder how such quirkiness survives in other areas like sales. Barbara Ehrenreich, in her recent book Bright-Sided, looks at corporations today – with their motivational speakers and “coaches” – and sees the same old demand for cheerful, optimistic obedience, especially in this era of outsourcing and downsizing.

The most popular technique for motivating the survivors of downsizing was “team building” – an effort so massive that it has spawned a “team-building industry” overlapping the motivation industry. . . .Or as Frank Loesser put it,

The literature and coaches emphasize that a good “team player” is by definition a “positive person.” He or she smiles frequently, does not complain, is not overly critical, and gracefully submits to whatever the boss demands.

FINCH: Your face is a company face.Here’s the whole song from the 1967 film version:

TWIMBLE: It smiles at executives then goes back in place.

The movie has another uncanny resemblance to today. The costumes and even the sets look like “Mad Men” – not surprising since both are set in the New York corporate world of the early 1960s. But there’s more. In the Broadway show and then the musical of “How to Succeed,” Robert Morse (Finch), rises to become head of advertising. Fifty years later, in “Mad Men,” Robert Morse (Bert Cooper) is the head of an advertising agency. (And he’s still wearing a bow tie.)

Baby Names and the Value on Distinctiveness

March 15, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

Namerology, the former Baby Name Voyager (here),is a great resource for anyone interested in graphs showing trends in baby names in the US. It uses the data from the Social Security Administration, but it’s graphs are much better than those you can create on the SSA Website. For instance, it allows you to compare names.

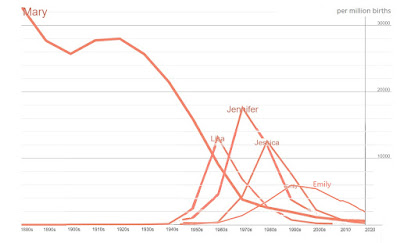

I wanted to explore the idea that the diversity of names is increasing. The most popular names today are not nearly as dominant as popular names in the past. It’s like TV shows. The ratings or share-of-audience of today’s most popular shows are numbers that twenty years ago would have marked them for cancellation. Compare the most popular name for girls born in the 1990s, Emily, with her counterpart in the 70s, Jennifer.

Jennifer’s peak was three times higher than Emily’s.

Jennifer also stacks up well against the top name of the sixties (Lisa) and of the eighties (Jessica).

Jennifer’s popularity was extraordinary. Jessica was at the top for nine of the eleven years from 1985 to 1995. And Lisa held top spot for eight years, 1962 - 1969. But Jennifer was number one for fifteen years, 1970-1984. We will probably never see her like again.

But then along comes Mary. The numbers for Mary back in the day dwarf those for Jennifer at the height of her popularity.

I read this graph to mean that the way we think about names has changed. Today, we just assume that you don’t want to give your kid the same name that everyone else has. You want something that different, but not too different. But a hundred years ago, distinctiveness was not important criterion for parents choosing a name. Year in year out, the girls name most often chosen was the same year in year out — Mary.

Names may be only part of a more general change in ides about children. Demographer Philip Cohen (here) speculates that compared with parents in the early 1900s, parents in the latter half of the twentieth-century saw each child as a unique individual. After all, children were becoming scarcer. From 1880 to 1940, the average number of children per family declined from 4.2 to 2.2, And while Mary remained the most popular name throughout that period, its market share declined from over 30,000 per million to about 20,000 per million.

The real shift starts in the 1960s. It may have been part of the general rejection of old cultural ways. But this was also the end of the baby boom. With new birth-control (the pill), having children became more a matter of choice. Family size declined even further. Each child was special and was deserving of a special name.

On Becoming a Beatles Listener

March 5, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

In the spring of 1964, I was getting a haircut in a barbershop in Tokyo. In the background a radio was playing American rock and pop. The sound was familiar even though I didn’t recognize any of the songs. I didn’t know any of the latest hits because I had spent the previous seven months in a small town up in the mountains. The family I was living with may have had a radio, but I cannot recall ever hearing it or what it played. The music I would hear on the variety shows on TV was all Japanese pop or sometimes Japanese versions of American hits. To this day, there are certain songs that were popular then — “Devil in Disguise” or “Bye-bye Birdie” — which in my mind’s ear I still hear in Japanese rather than English.

As I sat there, not really paying attention to the music, I realized that the song now playing was repeating the words “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” So this is it, I thought. This must be the Beatles that I’ve been reading about. The Japan Times, the English-language newspaper that came daily to the house, had run stories about them. It also showed the Billboard Top-20 each week, and I would see Beatles songs in several of the top slots. But in that barbershop that day, to me they sounded like the rest of the music that had been coming from the radio — conventional rock and roll.

I thought of that moment last month as I was reading David Brooks’s New York Times piece “What the Beatles Tell Us About Fame” (here). “How did the Beatles make it?” Brooks asks, and he gets the answer right. Partly. He sees that it’s not just about the music. Whether that music gets heard — recorded, distributed, played on the radio — depends on lots of non-musicians.

But hearing is not the same as liking. So how do the people who heard this music decide that they liked it, and liked it a lot? Brooks has a simplistic model for this process. “If a highly confident member of your group thinks something is cool, you’ll be more likely to think it’s cool,” as though the Beatles happened because influencers (they weren’t called that in 1963) were at work promoting them. But is that how people form their judgments of music? Surely we don’t think “Cool people like this so I’ll like it too.”

To understand how so many people come to share the idea that something is really great, we need a model more along the lines of Howie Becker’s “On Becoming a Marijuana User.” In that famous article, Becker identifies three necessary steps: learning the technique of smoking weed, learning to identify the effects, and learning to define those effects as pleasurable.

Of course, listening to rock and roll doesn’t require any special technique. But what about identifying the effects? As my barbershop experience illustrates, recognizing the Beatles is not automatic. Just as Becker’s marijuana users had to learn to perceive the effects of weed,* listeners had to learn to distinguish the Beatles sound from other music. That wasn’t the explicit goal of the people who listened to Beatles songs over and over, but it was an important side effect.

As for defining what we are hearing as great, the influence of others is not nearly so evident as it was among Becker’s pot smokers. In the diffusion of popularity, it doesn’t seem like anyone is learning or teaching. People around us are grooving to the Beatles, and so are we. Besides, millions of others have pushed these songs to the top of the charts, confirming our judgment that this stuff is the best. Popularity cascades upon itself. The more that the music becomes popular, the more of it you hear. The more familiar it becomes, the better it sounds. The process is less like instruction, more like contagion.

In November of 1963, my social geography — living in my small town in the Japan Alps — had quarantined me from the emotions that flooded Americans when Kennedy was assassinated. I did not feel what I would have felt if I had been in the US . (My 2013 post about that experience is here.) Five months later in that barber shop, I was listening to the Beatles, but I had not yet become a Beatles listener.

-----------

* Becker was doing his research among musicians in Chicago in the late 1940s and early 50s. Marijuana back then had nothing like the potency of today’s cultivars. Yet even now, other more experienced users are important in showing the neophyte user how to ingest the drug and how to appreciate the effects. Maureen Dowd’s famous unaccompanied fling with edibles (here) is a negative case in point.

Cotton-picking — Real and Metaphorical

February 24, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

Words change. Usually the change in the literal meaning is so gradual that it's hard to see. More visile may be the change in the political and emotional meanings that surround a word, and those meanings often depending on who is using it.

“Get your cotton-picking hands off that” is what the substitute teacher at Farmington High in Michigan said. The Black student she said it to couldn’t believe his ears. “What did you say?” She repeated it and explained. “This kind of comment was a very common comment. And it was a very innocent comment. It was not meant to be offensive in any way.”

The verb tense is important. The adjective “cotton-picking” was very common. I don’t know how old the substitute teacher is, but on the video, she does not sound young. (You can hear her on the video posted to TikTok.) She probably thinks of the word the way it was used in the previous century. Fifty years ago, cotton-picking was a word intellectuals might use to make a statement seem down-to-earth. Milton Friedman in 1979: “before government and OPEC stuck their cotton-picking fingers into the pricing of energy.” A character on a sitcom — a White, non-Southern character — might say, “Are you out of your cotton-picking mind?” It was funnier that way, believe me. It was a way of expressing disapproval but in a friendly, joking manner. White people used it as way to sound folksy and informal, perhaps in the way some well-educated, non-Southern people in this century have adopted “y’all.”

Google nGrams is not a good source on this one, but for what it’s worth, it shows cotton-picking as an adjective increasing till 1940 and declining steadily thereafter.

I suspect that nearly all of those instances from before 1950 were literal — things like references to cotton-picking machines. The metaphorical, disparaging cotton-picking came later. You can see this in the line for cotton-pickin’ since the dropped-g version would not have been used to talk about farm equipment. The earliest use the OED could find for this meaning was for this more colloquial spelling. It appeared in 1958, in the New York Post, which was then a liberal newspaper.* “I don’t think it's anybody’s cotton-pickin'’business what you’re doing.”

Of course, using cotton-picking this way worked only for people whose lives and world lay far from the actual picking of cotton. That was the world of the Michigan substitute teacher, and she used the word without ever thinking about its origins, in the same etymology-ignoring way we all speak. But for the Black kid, the word evoked the history of slavery and post-bellum racial exploitation in the Jim Crow South. And there was nothing friendly, funny, or folksy about it.

The teacher later said that she now realized that the term was offensive, but she maintained that her motives and intentions were innocent if ignorant. If only she had been — what’s the word here? If only there were a word that means aware of racist aspects of US history, aware of how privilege even today has a racial component, and sensitive to the ways those things might look to Black people. Wait, there is a word — “woke.” Or maybe I should say that there was a word. The political and emotional connotation has changed rapidly; so have the people who use it. And the change has been rapid. The people who use woke now are White, and they are waving it about as something to be rejected.

--------------

*The joke back then was that a front-page weather story in the Post might run with the headline: Cold Snap in City. Negroes, Jews Hardest Hit.

Applied Sociology, the Zeitgeist, and Why I Am Not Rich

February 20, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

I wonder how “Sex as Work” happened. (For those who don’t follow this blog regularly, i.e., everybody, I discussed this 1967 Social Problems article by Lionel Lewis and Dennis Brissett in the previous post.)

I imagine one of the authors mentioning, after a second or third beer one evening, that he had read a “marriage manual” not too long ago, whereupon his colleague confesses that he has too, though not the same one. “Not much fun in there that I could find.” “Not in the one I read either. What a letdown. I wonder if there are any others.” Thus are research studies born.

I’m surprised that “Sex as Work” ever got published. It has no statistical analysis, no quantitative data, not much data at all, just their take on fifteen “marriage manuals.” It reads more like something from a stand-up comic of the “observational” type. (“And what’s up with all this working on your technique? I mean, does anybody ever get off practicing scales on the piano?”) That and a really good title. In short, my kind of sociology. Yet it was the lead article in the flagship journal of the SSSP. Hey, it was the sixties.

Well, I said to myself when I had finished reading the article, that’s interesting and probably true, and it fits with other thoughts I have about American culture. And I closed the journal.

But what anyone with half a brain — the half with the money-making lobe — would have done is to call on their inner applied sociologist. And then they would have called on a publisher or literary agent. Here’s the elevator pitch:

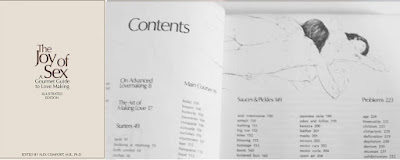

The only sex-instruction books around are from the fifties or have a fifties mentality. We’re now in sixties. This is the decade that began with the pill. People in the book-buying classes are having more sex with more partners, and they’ve stopped kidding themselves about marriage. They’re having sex younger and getting married older. And there are lots more divorces. Is anyone really going to buy A Doctor’s Marital Guide for Patients? (Yes, that’s one of the books in the ”Sex as Work” bibliography).Alas, I did not make that pitch, I did not write that book or suggest it to a publisher, and I did not get rich. But not long after, someone did. Alex Comfort. The book was The Joy of Sex, and it was in the top five books on the New York Times best-seller list for about a year and a half.

What they would buy is a book whose attitude towards sex is that it’s fun, a book without a medicinal smell, a book that doesn’t turn sex into goal-achievement through dogged technical mastery, a book that instead offers a tasting menu of all sorts of sexual activities.

The cover, inspired by The Joy of Cooking, is just plain text. The table of contents includes entries like “g-string, bondage, foursomes and moresomes, soixante-neuf, etc., as well as more traditional topics covered in “marriage manuals.”

I’m not a big believer in the Zeitgeist, but The Joy of Sex was a book whose time had come. Actually, its time had come a few years earlier, around the time that some sociologists were writing “Sex as Work” in an academic journal and other sociologists were reading it.

Sex and the Work Ethic

February 18, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

“Climax as Work,” the Gender and Society article I discussed in the previous post, caught my attention for the obvious reason. But I had another immediate reaction, one that I suspect is unique.

What the title called to my mind was another article, one published in the sociology journal Social Problems in 1967, before the authors of “Climax as Work” were born. The title: “Sex as Work” by Lionel Lewis and Dennis Brisset.* It was a content analysis of fifteen “marriage manuals” as they were called at the time, published in the 1950s and early 60s..

The authors start from the observation that “fun” in American culture had become a requirement. Americans judged themselves and others on the basis of what psychologist Martha Wolfenstein dubbed the “fun morality.” The irony is that making something a required part of the Protestant ethic largely takes the fun out of it. (See this post from sixteen years ago on how organizing kids’ sports inevitably crushes the fun.) The authors quote Nelson Foote: "Fun, in its rather unique American form, is grim resolve. . . .We are as determined about the pursuit of fun as a desert-wandering traveler is about the search for water.” As the title of the article implies, when it comes to sex, these marriage manuals see work as an absolutely necessary prerequisite for fun.

The work ethic in these books first of all emphasizes technical skill. The word technique appears frequently in the text, the chapter headings, and one of the book titles — Modern Sex Technique. Learning technique requires work. The books give cautions like, "Sexual relations are something to be worked at and developed.” “Sex is often something to be worked and strained at as an artist works and strains at his painting or sculpture.”

Work to acquire the requisite technique means study and preparation. One book refers to “study, training, and conscious effort.” Another, “If the two of them have through reading acquired a decent vocabulary and a general understanding of the fundamental facts listed above, they will in all likelihood be able to find their way to happiness.” Is this going to be on the midterm?

Like work, sex must proceed on a bureaucratic schedule. This means establishing a specific time for sex. But the manuals also break the sexual encounter into components much like an assembly line or a schedule of work activities, sometimes even specifying the time allotted to each. "Foreplay should never last less than fifteen minutes even though a woman may be sufficiently aroused in five.” Lewis and Brissett don’t mention it, but the scheduling mentality was also the basis for what some of the manuals saw as the ideal product — simultaneous orgasm. The partners here are much like workers who must co-ordinate their separate activities to arrive at the same place at the same time.

Lewis and Brissett also fail to mention other things that now seem obvious. First, these books are “marriage manuals” not “sex manuals.” They imply not only that sex is limited to married couples but that it is an obligation stipulated in the marriage contract.

Second, these books frame sex not just as technical and bureaucratic but as medical. Ten of the fifteen books have authors with M.D. after their name; others have Ph.D. Only three authors are uncredentialed. The M.D. or Ph.D. speaks from a position of authority, authority based on their own technical expertise. This too seems at odds with any notion of fun or pleasure. We rarely think of consulting a doctor as “fun,” perhaps even less so for consulting a Ph.D.

In any case, Lewis and Brissett had spotted the most important aspect of these sex books, one that nobody else seemed to have noticed. The insights of “Sex as Work” pointed to an obvious next step. Or maybe it wasn’t so obvious. If it had been, I might be rich. But I’ll leave that for the next post.

------------------------

* The full title of the article is “Sex as Work: A Study of Avocational Counseling.” Social Problems, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Summer, 1967), pp. 8-18