May 4, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

“The Marvelous Mrs. Anachronism” (here) is the post in this blog with by far the most hits and comments. And now we have “Julia,” the HBO series about Julia Child and the creation of her TV show “The French Chef.” It’s set in roughly the same time period, the early 1960s. And like “Mrs. Maisel,” it offers a rich tasting menu of anachronisms.

I don’t know why the producers don’t bother to check their scripts with someone who was around in 1962 – a retired sociologist, say, who is sensitive to language – but they don’t. Had they done so, they would have avoided the linguistic equivalent of a digital microwave in the kitchen and a Prius in the driveway. They would not have had a character say, “I’m o.k. with it.” Nor would an assistant assigned a task say, “I’m on it.” Nobody working with Julia would be excited to be on the front lines of “your process.” “Your method” perhaps or “your approach” or even “all that you do,” but not “your process.”

If you’re a TV writer, even an older writer of fifty or so, these phrases have been around for as long as you can remember, so maybe you assume they’ve always been part of the language.

But they haven’t. Sixty years ago, people might have asked how some enterprise made money or at least made ends meet. But they would not have asked it the way Julia’s father asks her: “What's the business model down there? Does public television even* have a business model?”

In her equally anachronistic reply, Julia says, “Nothing's a done deal yet,” That one too sounded wrong. I don’t recall any done deals in 1962.

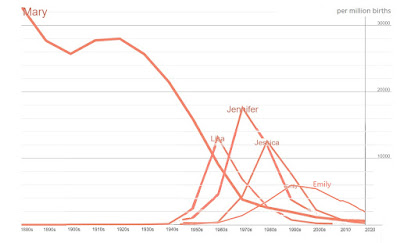

To check my memory, I went to Google nGrams. It shows the frequency of words and phrases as they occur in books. Most of the phrases that seemed off to my ear did not appear in books until the 1980s. A corpus of the language as spoken would have been better, and there’s a lag of a few years before new usages on the street make it to the printed page. But that lag time is certainly not the twenty years that nGrams finds.

In another episode, we hear “cut to the chase,” but it was not till the 80s that we skipped over less important details by cutting to the chase. (Oh well, at least nobody on “Julia” abbreviated a narrative with “yada yada.”) Or again, a producer considering the possibilities of selling the show to other stations says, “This could be game changer.” But “game changer” didn’t show up in books until four decades after “The French Chef” went on the air.

“This little plot is genius,” says Julia’s husband. It may have been, but in 1962, genius was not an adjective. An unusual solution to a problem might be ingenious, but it was not simply “genius.” Even more incongruous was Julia’s telling the crowd that shows up for a book signing in San Francisco, “I'm absolutely gobsmacked by this turnout.” Gobsmacked originated in Britain, but even in her years abroad, Julia would not have heard the term. Brits weren’t gobsmacked until the late 1970s, with Americans joining the chorus a decade or so later.

I heard other dubious terms that I did not know how to check. “The Yankees are toast,” says one character, presumably a Red Sox fan. It’s not just that in 1962 the Yankees were anything but toast, winning the AL pennant and the World Series; I doubt that anyone was “toast” sixty years ago.

The one that bothered me most was what Julia’s friend Avis says after making a small play on words. She adds, “See what I did?” I’m pretty sure this is a very recent usage and was not around in 1962. I’d just as soon not have it around today.

Finally, in the latest episode, which I just now saw and which inspired me to write this post, we have the anachronism that nobody notices — “need to” instead of “should” or “ought to” or other words that carry a hint of what is right or even moral. In “Julia,” a young couple meet for lunch at a diner. It’s a blind date, and as they talk, it becomes clear that they are a good match. They talk some more, and we cut to a different plot line. When we come back to the diner, the couple are still there, still talking, but they are now the only ones left in the place. The waitress comes to the table and tells them patiently, “You need to go.”

What she means of course is that she needs for them to go. In 1962, she would not have phrased it in terms of their needs. She would have said, “You have to go.”

-------------------------------

* “Even” as an intensifier in this way may also not have come into use until much later in the century. See this Language Log post on “What does that even mean?”