December 30, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Scatterplot has had a discussion about campus visits for job candidates. Good timing – at Montclair, we’ve just completed a search. We reviewed several dozen applications and had two people come to campus for interviews. But why?

Interview isn’t quite the right word. Neither is ordeal, though it comes closer. The person spends an entire day on campus: there’s morning coffee, then The Talk presenting her research, informal chats and lunch with faculty, an interview with the dean, maybe teaching a sample class, a campus tour, dinner with faculty.

I’ve become convinced that these visits are useful only for seeing how you’ll get along socially, not for anything truly academic. It’s sort of like a first date or, in societies with arranged marriages, the pre-wedding meeting that a couple may have. And about as useful for predicting compatibility.

For the task part of the job, for gauging how the person will be as a scholar and teacher, the campus visit may be worse than no visit at all.

That’s especially true for teaching. We used to ask candidates to do a sample class. This time around, we dropped that requirement, though for logistical reasons not methodological ones. Still, it was the right decision.

A class session taught by a job applicant is anecdotal evidence, and it puzzles me that a group of social scientists would use it at all.

It’s not just anecdotal evidence, it’s unrepresentative anecdotal evidence. You have your candidate teach one session of another teacher’s course – students she’s never seen before and as many as half a dozen faculty members watching from the back of the room.

Nevertheless, just as the dramatic story is often more convincing than a ream of statistics, seeing someone in person can outweigh more systematic data, even for sociologists, who should know better.

In discussing the candidate later, when someone cites the outstanding evaluations the person has received in several courses at her home university, someone else might say, “Well, she didn’t seem so good with our students,” as if this bit of anecdotal evidence wiped out the systematic evidence of the all those evaluations.

As Stalin is supposed to have said, “The death of a million Russian soldiers, that is a statistic; the death a single Russian soldier, that is a tragedy.” And even among sociologists, statistics can be less compelling than tragedy.

A blog by Jay Livingston -- what I've been thinking, reading, seeing, or doing. Although I am an emeritus member of the Montclair State University department of sociology, this blog has no official connection to Montclair State University. “Montclair State University does not endorse the views or opinions expressed therein. The content provided is that of the author and does not express the view of Montclair State University.”

Subscribe via Email

The Job Interview - Anecdotal Data

Palm Christmas

December 24, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

A Wall Street Journal article by John Steele Gordon reminds me how deeply entrenched in my mind are the images of Christmas – all those wintry images of snowmen and skaters, pine trees with tinsel icicles, chestnuts roasting, and all the rest. Then I got down here to Florida. The decorations were the same – stockings, wreaths, Santas. But they were framed in palm trees, and I was wearing shorts.

Those Christmas lights should be reflecting off the snow, not off the water in the marina.

Gordon notes that the Christmas I’m thinking of is a fairly recent creation and has little to do with the birth of Jesus (which is O.K. with me). I’ve visited Bethlehem, and it didn’t seem like the sort of place you’d find Frosty the Snowman, even in December. (And as Gordon says, it’s likely that the actual date of Jesus’s birth was in the spring or summer, when shepherds abide in the fields, not in the winter, when the flocks are in the corral.)

Even the holiday shopping didn’t have the same feel as it does in cold weather. Here, it just seemed like a lot of people in Best Buy.

No, this is more what I had in mind (I took this one last week).

Posted by Jay Livingston

The sun is shining, the grass is green

The orange and palm trees sway . . .

But it's December the twenty-fourth . . .

Those Christmas lights should be reflecting off the snow, not off the water in the marina.

Gordon notes that the Christmas I’m thinking of is a fairly recent creation and has little to do with the birth of Jesus (which is O.K. with me). I’ve visited Bethlehem, and it didn’t seem like the sort of place you’d find Frosty the Snowman, even in December. (And as Gordon says, it’s likely that the actual date of Jesus’s birth was in the spring or summer, when shepherds abide in the fields, not in the winter, when the flocks are in the corral.)

Even the holiday shopping didn’t have the same feel as it does in cold weather. Here, it just seemed like a lot of people in Best Buy.

No, this is more what I had in mind (I took this one last week).

MERRY CHRISTMAS TO ALL

Schmucks With Powerbooks

December 19, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Americans usually think about class as money. But there are still areas where structural position and power trump income. Athletes, in strict Marxian terms, are part of the proletariat. They toil for wages, they have a union.

They aren’t the only well-paid workers of the world with a working-class consciousness. As we speak, some very well paid writers of movies and TV shows are walking the picket lines. The studios made an offer last week which they claim will pay writers an average of $230,000 a year. The Writers Guild considered it an insult. The offer and the claim were misleading, but even if they were accurate, the Marxian class division – bourgeoisie and proletariat, owners and workers – would still hold.

even if they were accurate, the Marxian class division – bourgeoisie and proletariat, owners and workers – would still hold.

Nearly thirty years ago, Ben Stein wrote a book about the way Hollywood writers portrayed America (The View from Sunset Boulevard, 1979). The writers were making what by most standards was a lot of money. Stein, a conservative then and now, seemed to be especially puzzled by their demonization of business and wealth, not just in the scripts they wrote but in their private beliefs.

But a few pages later, Stein describes the structural position of the writer in classic Marxist terms:

The LA Times has been running a good colloquy – or “dust-up” as they call it – between a writer and a media mogul discussing the strike. You can find it here.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Americans usually think about class as money. But there are still areas where structural position and power trump income. Athletes, in strict Marxian terms, are part of the proletariat. They toil for wages, they have a union.

They aren’t the only well-paid workers of the world with a working-class consciousness. As we speak, some very well paid writers of movies and TV shows are walking the picket lines. The studios made an offer last week which they claim will pay writers an average of $230,000 a year. The Writers Guild considered it an insult. The offer and the claim were misleading, but

even if they were accurate, the Marxian class division – bourgeoisie and proletariat, owners and workers – would still hold.

even if they were accurate, the Marxian class division – bourgeoisie and proletariat, owners and workers – would still hold.Nearly thirty years ago, Ben Stein wrote a book about the way Hollywood writers portrayed America (The View from Sunset Boulevard, 1979). The writers were making what by most standards was a lot of money. Stein, a conservative then and now, seemed to be especially puzzled by their demonization of business and wealth, not just in the scripts they wrote but in their private beliefs.

Even those with millions of dollars believed themselves to be part of a working class distinctly at odds with the exploiting classes – who, if the subject came up, were identified as the Rockefellers and multinational corporations. For an obscure reason,(Stein was a big Nixon fan and obviously sensitive to any mention of the name of his hero. He’d been a Nixon speechwriter, and some years later – I wish I could track down this quote – he said that Nixon had “the soul of a poet.”)the name of Nixon was also thrown in frequently.

But a few pages later, Stein describes the structural position of the writer in classic Marxist terms:

The Hollywood TV writer . . . is actually in a business, selling his labor to brutally callous businessmen. One actually has to go through that experience of writing for money in Hollywood or anywhere else to realize just how unpleasant it is. Most of the pain comes from dealings with business people, such as agents or business affairs officers of production companies and networks.And the current clash seems to be over surplus value (another Marxian term) in the form of residuals. It’s also about the owners’ expropriation of the workers’ product, for regardless of who actually creates the words in a script, the legal author of a movie is the studio. And I also suspect that at some level it’s about respect. I get the sense that the studios’ basic view of their employees hasn’t much changed since the days of Jack Warner, who said famously

Actors – schmucks. Writers – schmucks with Underwoods.Except now the schmucks have Powerbooks, agents, and unions.

The LA Times has been running a good colloquy – or “dust-up” as they call it – between a writer and a media mogul discussing the strike. You can find it here.

Labels:

Movies TV etc.

Jocks - Wealth vs. Power

December 18, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Phil, in his comment on the previous post, says that as food for thought, he asks students “to chew on the class position of David Beckham.” How to reconcile the fabulous incomes of these sports stars with their subjugated structural position? True, Beckham and Barry Bonds are not exactly the proletariat of Dickensian London. But they do earn most of their money, whether on the field or from endorsements, by working for the owners. They have much wealth but relatively little power. Is the fault in our superstars, dear Beckham, in our Marxist theories, or in sport itself?

William Rhoden, a sports writer for the New York Times, argues that black athletes, even the very well paid, are still the exploited. They are Forty Million Dollar Slaves, and when they threaten to revolt or seize some small bit of power, the white establishment reacted strongly to retain control. We all know what happened to Ali when he challenged the Vietnam war, and if we’ve seen The Great White Hope, we know about Jack Johnson. But who knows about Rube Foster, who tried to form a baseball league with black-owned teams?

threaten to revolt or seize some small bit of power, the white establishment reacted strongly to retain control. We all know what happened to Ali when he challenged the Vietnam war, and if we’ve seen The Great White Hope, we know about Jack Johnson. But who knows about Rube Foster, who tried to form a baseball league with black-owned teams?

What’s interesting – and disappointing to Rhoden – is how few black athletes have used their wealth to move into positions of ownership. Successful musicians start their own record labels or even clothing lines (P. Diddy). But athletes, white or black, have not become brands, nor even noticeably entrepreneurs or owners. It’s Jay-Z, not some former athlete, who’s a co-owner of the Nets.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Phil, in his comment on the previous post, says that as food for thought, he asks students “to chew on the class position of David Beckham.” How to reconcile the fabulous incomes of these sports stars with their subjugated structural position? True, Beckham and Barry Bonds are not exactly the proletariat of Dickensian London. But they do earn most of their money, whether on the field or from endorsements, by working for the owners. They have much wealth but relatively little power. Is the fault in our superstars, dear Beckham, in our Marxist theories, or in sport itself?

William Rhoden, a sports writer for the New York Times, argues that black athletes, even the very well paid, are still the exploited. They are Forty Million Dollar Slaves, and when they

threaten to revolt or seize some small bit of power, the white establishment reacted strongly to retain control. We all know what happened to Ali when he challenged the Vietnam war, and if we’ve seen The Great White Hope, we know about Jack Johnson. But who knows about Rube Foster, who tried to form a baseball league with black-owned teams?

threaten to revolt or seize some small bit of power, the white establishment reacted strongly to retain control. We all know what happened to Ali when he challenged the Vietnam war, and if we’ve seen The Great White Hope, we know about Jack Johnson. But who knows about Rube Foster, who tried to form a baseball league with black-owned teams?What’s interesting – and disappointing to Rhoden – is how few black athletes have used their wealth to move into positions of ownership. Successful musicians start their own record labels or even clothing lines (P. Diddy). But athletes, white or black, have not become brands, nor even noticeably entrepreneurs or owners. It’s Jay-Z, not some former athlete, who’s a co-owner of the Nets.

Labels:

Sport

Driven to Distractors

December 16, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

My final exam will have some multiple-choice questions. I write my own, and it’s sometime hard to come up with good wrong choices, or “distractors” as people in the test-making biz call them. I always try to have at least a couple of questions with one amusing distractor. For example,

The risk, of course, is that the distractor you thought was so ludicrous it would get a chuckle – usually at least one student chooses it. Wait, maybe that’s it – instead of Chuck Berry, Ludacris.

Posted by Jay Livingston

My final exam will have some multiple-choice questions. I write my own, and it’s sometime hard to come up with good wrong choices, or “distractors” as people in the test-making biz call them. I always try to have at least a couple of questions with one amusing distractor. For example,

A janitor makes $8 an hour; Barry Bonds makes tens of millions a year playing baseball. Why might Marx classify both men as members of the same social class?It's the last choice that's supposed to elicit a small smile, though I prefer a distractor that's truly silly.

a. They are both in occupations that have uncertain career paths.

b. They are both in occupations that do not require extensive education.

c. They are both selling their labor to someone who owns the means of production.

d. They are both in occupations that have many minorities.

e. They are both in occupations that don’t have very good tests for steroids.

In Durkheim’s view, the god or gods that a society worshiped were a representation ofI stole that one from an old Monty Python page (The Hackenthorpe Book of Lies), and maybe Chuck Berry isn’t le distractor juste for students born in 1986. I’m open to suggestions for better distractors . . . and better questions.

a. The society itself

b. The unknowable

c. An authoritarian father

d. Chuck Berry

The risk, of course, is that the distractor you thought was so ludicrous it would get a chuckle – usually at least one student chooses it. Wait, maybe that’s it – instead of Chuck Berry, Ludacris.

Bothered in Translation

December 12, 2007

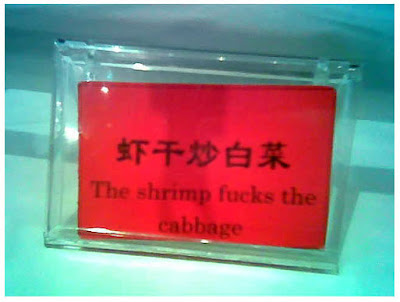

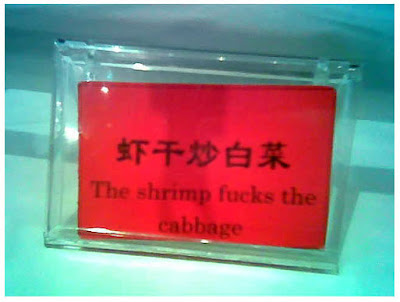

Posted by Jay Livingston

Dan Myers has an amusing post today reprinting the transcript from his computer's dictation software.

Here's further evidence that language still presents problems for computers.

Apparently this mistranslation is widespread in China - in supermarkets (as above), in restaurants (as below), and elsewhere.

Victor Mair at The Language Log makes a strong case that the source of the error is not human malice or mischief but the machine translation of a simplified Chinese ideogram.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Dan Myers has an amusing post today reprinting the transcript from his computer's dictation software.

Here's further evidence that language still presents problems for computers.

Apparently this mistranslation is widespread in China - in supermarkets (as above), in restaurants (as below), and elsewhere.

Victor Mair at The Language Log makes a strong case that the source of the error is not human malice or mischief but the machine translation of a simplified Chinese ideogram.

Sleepless Nights

December 10, 2007Posted by Jay Livingston

Sleepless Nights is what I remember. It’s a novel that seems more like a memoir, that might well be a memoir. New York in the forties and fifties (as in the above passage), Louisville in the twenties and thirties.

Sleepless Nights is what I remember. It’s a novel that seems more like a memoir, that might well be a memoir. New York in the forties and fifties (as in the above passage), Louisville in the twenties and thirties.

Here’s a relgious campground of her youth:

Living in New York in the forties, she went to jazz clubs to hear Billie Holiday:

You should read this book if only for the prose style. O.K., it’s not sociology, but it’s a finely observed rendering of these times and places and her life there.

That’s Elizabeth Hardwick, who died a week ago. The obits said that she was best known as an essayist, a co-founder of the New York Review and wife, for a time, of Robert Lowell. But

I have left out my abortion, left out running from the pale, frightened doctors and their sallow, furious wives in the grimy, curtained offices on West End Avenue. What are you screaming for? I have not even touched you, the doctor said. His wife led me to the door, her hand as firmly and punitively on my arm as if she had been a detective making an arrest. Do not come back ever.

I ended up with a cheerful, never-lost-a-case black practitioner, who smoked a cigar throughout. When it was over he handed me his card. It was an advertisement for the funeral home he also operated. Can you believe it, darling? he said.

Sleepless Nights is what I remember. It’s a novel that seems more like a memoir, that might well be a memoir. New York in the forties and fifties (as in the above passage), Louisville in the twenties and thirties.

Sleepless Nights is what I remember. It’s a novel that seems more like a memoir, that might well be a memoir. New York in the forties and fifties (as in the above passage), Louisville in the twenties and thirties.Here’s a relgious campground of her youth:

Under the string of light bulbs in the humid tents, the desperate and unsteady human wills struggle for a night against the fierce pessimism of experience and the root empiricism of every troubled loser . . . .Perhaps here began a prying sympathy for the victims of sloth and recurrent mistakes, sympathy for the tendency of lives to obey the laws of gravity and to sink downward, falling as gently and slowly as a kite, or violently breaking and crashing.She did not stay long in the church

Seasons of nature and seasons of experience that appear as a surprise but are merely the arrival of the calendar’s predictions. Thus the full moon of excited churchgoing days and the frost of apostasy as fourteen arrives.

Living in New York in the forties, she went to jazz clubs to hear Billie Holiday:

The creamy lips, the oily eyelids, the violent perfume – and in her voice the tropical l’s and r’s. Her presence, her singing, created a large, swelling anxiety. . . . Here was a woman who had never been a Christian. . . . .Sometimes she dyed her hair red and the curls lay flat against her skull, like dried blood.She had heard jazz back in Louisville – Ellington, Chick Webb – but it was different:

When I speak of the great bands it must not be taken to mean that we thought of them as such. No, they were part of the summer nights and the hot dog stands, the fetid swimming pool heavy with chlorine, the screaming roller coaster, the old rain-splintered picnic tables, the broken iron swings. And the bands were also part of the Southern drunkenness, couples drinking Coke and whiskey, vomiting, being unfaithful, lovelorn, frantic. The black musicians, with their cumbersome instruments, their tuxedos, were simply there to beat out time for the stumbling, cuddling fox-trotting of the period.

You should read this book if only for the prose style. O.K., it’s not sociology, but it’s a finely observed rendering of these times and places and her life there.

Labels:

Print

Torture, Execution, and Conservative Morality

December 8, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Mark Kleiman, prime mover of The Reality-Based Community, asks why it is that people on the Hard Right reject candidates who have reservations about torture and capital punishment. What is it about these practices that they find so appealing?

To his credit, Mark doesn’t merely dismiss them as sadists, at least not all of them. Instead, he writes:

He’s not wrong, but I think Jonathan Haidt’s work on morality provides a more complete way of understanding the problem. Liberals in the Western industrialized world, says Haidt, evaluate morality on two dimensions:

My own hunch is that ingroup/loyalty is the most important, especially in the debate over torture and the death penalty. The terrorist and the convicted killer stand on the other side of our society’s moral boundary. They are not part of our group; in fact, they are a danger to it. They are, therefore, not protected by the morality that we apply to people within our group – the loyalty factor trumps all others – so anything we do to them in the name of protecting our group is morally justified.

And, as Kleiman notes, ideology takes precedence over evidence of actual effectiveness.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Mark Kleiman, prime mover of The Reality-Based Community, asks why it is that people on the Hard Right reject candidates who have reservations about torture and capital punishment. What is it about these practices that they find so appealing?

To his credit, Mark doesn’t merely dismiss them as sadists, at least not all of them. Instead, he writes:

But even people who take no personal joy in imagining the torture of enemies may take support for torture as a positive sign in evaluating a candidate. A candidate who supports torture (1) displays an unlimited, as opposed to a merely conditional, willingness to fight terrorism and (2) displays andreia, “manliness.”

He’s not wrong, but I think Jonathan Haidt’s work on morality provides a more complete way of understanding the problem. Liberals in the Western industrialized world, says Haidt, evaluate morality on two dimensions:

- harm/care

- fairness/justice

- ingroup/loyalty

- authority/respect

- purity/sanctity

My own hunch is that ingroup/loyalty is the most important, especially in the debate over torture and the death penalty. The terrorist and the convicted killer stand on the other side of our society’s moral boundary. They are not part of our group; in fact, they are a danger to it. They are, therefore, not protected by the morality that we apply to people within our group – the loyalty factor trumps all others – so anything we do to them in the name of protecting our group is morally justified.

And, as Kleiman notes, ideology takes precedence over evidence of actual effectiveness.

the consequentialist arguments (the death penalty deters/torture extracts useful information) are largely afterthoughts.Purity, loyalty, respect – basically it’s Mafia morality, a morality which, as I blogged a while ago, has a deep appeal to many Americans.

The Subprime Thing For Dummies

December 7, 2008

Posted by Jay Livingston

I like simplified explanations of complicated economic stuff I don't understand. The more pictures and fewer words, the better. So I was very please to find this graphic flow chart created by Felix Salmon at Portfolio.com to explain CDOs, RMBSs, tranches, and the whole subprime mortgage fiasco.

I can’t figure out how to get Blogspot to print the graphic as large as it needs to be for you to read the text box. But you can find the whole show here.

I can’t figure out how to get Blogspot to print the graphic as large as it needs to be for you to read the text box. But you can find the whole show here.

Posted by Jay Livingston

I like simplified explanations of complicated economic stuff I don't understand. The more pictures and fewer words, the better. So I was very please to find this graphic flow chart created by Felix Salmon at Portfolio.com to explain CDOs, RMBSs, tranches, and the whole subprime mortgage fiasco.

I can’t figure out how to get Blogspot to print the graphic as large as it needs to be for you to read the text box. But you can find the whole show here.

I can’t figure out how to get Blogspot to print the graphic as large as it needs to be for you to read the text box. But you can find the whole show here.

This Takes the Cake

December 6, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

I'm not sure what the sociological import of this is, and you may have already seen it as it whirls around the Internet. But since my previous post ended with a ritual cake, this is sort of a follow-up.

Apparently someone phoned the bakery at Wal-mart and ordered a customized cake for a co-worker who was leaving. When asked what message was to go on the cake, the caller probably said something like, “OK, here's what I want: 'Best Wishes Suzanne' ; underneath that, 'We will miss you.'”

Here's the cake:

Posted by Jay Livingston

I'm not sure what the sociological import of this is, and you may have already seen it as it whirls around the Internet. But since my previous post ended with a ritual cake, this is sort of a follow-up.

Apparently someone phoned the bakery at Wal-mart and ordered a customized cake for a co-worker who was leaving. When asked what message was to go on the cake, the caller probably said something like, “OK, here's what I want: 'Best Wishes Suzanne' ; underneath that, 'We will miss you.'”

Here's the cake:

Sweat Equity and Magical Thinking

December 3, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Remember the Seinfeld episode about wiping the exercise machine at the gym? (To see it, go here, push the slider to 16:30 and watch for 50 seconds.)

There I was at the gym in Florida on the elliptical machine (the machine that won’t come right out and say what it means), sweating and thinking about sweat. The fitness room at the condo enclave in Sarasota where my mother lives has a spray bottle (disinfectant? soap?) and paper towels, and everyone sprays and wipes the machine when they finish. I guess it’s so you don’t contract what they have, which seems mostly to be old age.

But I think Elaine had it right. Sweat is about social contagion, not medical contagion. It’s part of magical thinking – the idea that a person’s essence, spirit, power, mana, or whatever you want to call it can be transmitted physically by touch and by those things that were once part of the body. Hair is often the medium of choice, whether for voodoo or lockets. And wasn’t someone selling some celebrity’s hair on eBay? But we can also use fingernail parings, clothes, breath, or especially, precious bodily fluids

So sweat can be gross or it can valuable, depending on the source. If it’s just another struggling exerciser, we spray and wipe lest we be touched with their mundane germs. But if it’s someone whose magic we want to capture or someone we want to be connected to, that sweat is just what we need.

I kept pedaling, going nowhere fast, following this train of thought, and watching MTV. In the afternoon, viewing choice at the gym is limited, and I wasn’t up for the stock market channel or the soaps. “My Super Sweet Sixteen” was just coming to a close. A girl at the party was holding up a CD of the rap star who’d been hired for the party. “I got him to wipe some of his sweat on it,” she beamed ecstatically. The sweat transmitted his superstar magic to the CD. By touching the CD, she was now touching him and acquiring some of that magic.

Birthday parties themselves follow this same logic of magical thinking. We make the birthday girl or boy superstar for a day. We invest her or him with this magic power, and then we capture it. How?

After the sweaty CD moment, the camera panned over to the birthday girl leaning over her cake. With one long, sweeping breath, she blew out the sixteen candles. The show ended before the cutting and serving of the cake, but here’s the point: Suppose someone invites you to dine. You finish the appetizer and main course, and then your friend says, “I want you to have this wonderful pastry for dessert. But before I serve it to you, I’m going to breathe heavily all over it at close range.” He proceeds to do just that and then hands you the pastry.

Under most circumstances, we’d resent the offer as unsanitary. But at a birthday party. . . .

UPDATE, Feb. 2013: In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council has issued guidelines recommending that children not be allowed to blow out the candles. (Time has the story.)

Posted by Jay Livingston

Remember the Seinfeld episode about wiping the exercise machine at the gym? (To see it, go here, push the slider to 16:30 and watch for 50 seconds.)

| Elaine and Greg at the health club. A sweaty Greg is exercising on a leg machine. ELAINE: Hi, Greg. GREG: Hey, Elaine. I'll be off in a second. Another guy approaches the exercise machine. ELAINE: I got the machine next, buddy. Greg finishes up his workout and gets off the machine. GREG (to Elaine): It's all yours. Walks away. Elaine looks at the machine, then George runs over. GEORGE: What happened? Did he bring it up? ELAINE: Never mind that, look at the signal I just got. GEORGE: Signal? What signal? ELAINE: Lookit. He knew I was gonna use the machine next, he didn't wipe his sweat off. That's a gesture of intimacy. GEORGE: I'll tell you what that is - that's a violation of club rules. Now I got him! And you're my witness! ELAINE: Listen, George! Listen! He knew what he was doing, this was a signal. GEORGE: A guy leaves a puddle of sweat, that's a signal? ELAINE: Yeah! It's a social thing. GEORGE: What if he left you a used Kleenex, what's that, a valentine? |

There I was at the gym in Florida on the elliptical machine (the machine that won’t come right out and say what it means), sweating and thinking about sweat. The fitness room at the condo enclave in Sarasota where my mother lives has a spray bottle (disinfectant? soap?) and paper towels, and everyone sprays and wipes the machine when they finish. I guess it’s so you don’t contract what they have, which seems mostly to be old age.

But I think Elaine had it right. Sweat is about social contagion, not medical contagion. It’s part of magical thinking – the idea that a person’s essence, spirit, power, mana, or whatever you want to call it can be transmitted physically by touch and by those things that were once part of the body. Hair is often the medium of choice, whether for voodoo or lockets. And wasn’t someone selling some celebrity’s hair on eBay? But we can also use fingernail parings, clothes, breath, or especially, precious bodily fluids

So sweat can be gross or it can valuable, depending on the source. If it’s just another struggling exerciser, we spray and wipe lest we be touched with their mundane germs. But if it’s someone whose magic we want to capture or someone we want to be connected to, that sweat is just what we need.

I kept pedaling, going nowhere fast, following this train of thought, and watching MTV. In the afternoon, viewing choice at the gym is limited, and I wasn’t up for the stock market channel or the soaps. “My Super Sweet Sixteen” was just coming to a close. A girl at the party was holding up a CD of the rap star who’d been hired for the party. “I got him to wipe some of his sweat on it,” she beamed ecstatically. The sweat transmitted his superstar magic to the CD. By touching the CD, she was now touching him and acquiring some of that magic.

Birthday parties themselves follow this same logic of magical thinking. We make the birthday girl or boy superstar for a day. We invest her or him with this magic power, and then we capture it. How?

After the sweaty CD moment, the camera panned over to the birthday girl leaning over her cake. With one long, sweeping breath, she blew out the sixteen candles. The show ended before the cutting and serving of the cake, but here’s the point: Suppose someone invites you to dine. You finish the appetizer and main course, and then your friend says, “I want you to have this wonderful pastry for dessert. But before I serve it to you, I’m going to breathe heavily all over it at close range.” He proceeds to do just that and then hands you the pastry.

Under most circumstances, we’d resent the offer as unsanitary. But at a birthday party. . . .

UPDATE, Feb. 2013: In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council has issued guidelines recommending that children not be allowed to blow out the candles. (Time has the story.)

Labels:

Ritual

More Worlds in Collision

December 1, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

I posted something recently about the new problems of “audience segregation” created by Facebook and other social networking sites. I had forgotten about a Washington Post article from last June that Eszter had linked to.

The students at a Bethesda high school had a worlds-in-collision experience when they opened their yearbooks and found pictures that the yearbook editors had downloaded from their Facebook pages. The yearbook staff weren’t trying to be stalkers. But they hadn’t taken enough photos themselves, and they were pressed for time, so they went to the Internet and grabbed Facebook photos off friends’ pages. (If this scenario sounds like the one usually associated with plagiarised papers, that’s because it is. Essays, photos, whatever.)

Facebook users can restrict who has access to their pages, an arrangement which sounds like it ensures some degree of privacy. But on second thought, it means that you have entrusted your privacy, your audience control, to all those you designate as friends. It takes only one “friend” facing a yearbook deadline to shatter that wall of privacy. And suddenly the world can see that picture of you and your friends, with your goofy poses and red plastic cups.

Posted by Jay Livingston

I posted something recently about the new problems of “audience segregation” created by Facebook and other social networking sites. I had forgotten about a Washington Post article from last June that Eszter had linked to.

The students at a Bethesda high school had a worlds-in-collision experience when they opened their yearbooks and found pictures that the yearbook editors had downloaded from their Facebook pages. The yearbook staff weren’t trying to be stalkers. But they hadn’t taken enough photos themselves, and they were pressed for time, so they went to the Internet and grabbed Facebook photos off friends’ pages. (If this scenario sounds like the one usually associated with plagiarised papers, that’s because it is. Essays, photos, whatever.)

Facebook users can restrict who has access to their pages, an arrangement which sounds like it ensures some degree of privacy. But on second thought, it means that you have entrusted your privacy, your audience control, to all those you designate as friends. It takes only one “friend” facing a yearbook deadline to shatter that wall of privacy. And suddenly the world can see that picture of you and your friends, with your goofy poses and red plastic cups.

“We grew up with the idea that you can share anything you want with your friends through the Internet," said Amy Hemmati, 16, a rising Walter Johnson junior. “I think we're very trusting in the online community, as opposed to adults, who are on the outside looking in.”

Gee Whiz

November 28, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Some time ago, the comments on a post here brought up the topic of the “gee whiz graph.” Recently, thanks to a lead from Andrew Gelman , I’ve found another good example in a recent paper.

The authors, Leif Nelson and Joseph Simmons, have been looking at the influence of initials. Their ideas seem silly at first glance (batters whose names begin with K are more likely to strike out), like those other name studies that claim people named Dennis are more likely to become dentists while those named Lawrence or Laura are more likely to become lawyers

But Nelson and Simmons have the data. Here’s their graph showing that students whose last names begin with C and D get lower grades than do students whose names begin with A and B.

The graph shows an impressive difference, certainly one that warrants Nelson and Simmon’s explanation:

The graph shows an impressive difference, certainly one that warrants Nelson and Simmon’s explanation:

Notice that “slightly.” To find out how slight, you have to take a second look at the numbers on the axis of that gee-whiz graph. The Nelson-Simmons paper doesn’t give the actual means, but from the graph it looks as though the A students’ mean is not quite 3.37. The D students average between 3.34 and 3.35, closer to the latter. But even if the means were, respectively, 3.37 and 3.34, that’s a difference of a whopping 0.03 GPA points.

When you put the numbers on a GPA axis that goes from 0 to 4.0, the differences look like this.

According to Nelson and Simmons, the AB / CD difference was significant (F = 4.55, p < .001). But as I remind students, in the language of statistics, a significant difference is not the same as a meaningful difference.

According to Nelson and Simmons, the AB / CD difference was significant (F = 4.55, p < .001). But as I remind students, in the language of statistics, a significant difference is not the same as a meaningful difference.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Some time ago, the comments on a post here brought up the topic of the “gee whiz graph.” Recently, thanks to a lead from Andrew Gelman , I’ve found another good example in a recent paper.

The authors, Leif Nelson and Joseph Simmons, have been looking at the influence of initials. Their ideas seem silly at first glance (batters whose names begin with K are more likely to strike out), like those other name studies that claim people named Dennis are more likely to become dentists while those named Lawrence or Laura are more likely to become lawyers

But Nelson and Simmons have the data. Here’s their graph showing that students whose last names begin with C and D get lower grades than do students whose names begin with A and B.

The graph shows an impressive difference, certainly one that warrants Nelson and Simmon’s explanation:

The graph shows an impressive difference, certainly one that warrants Nelson and Simmon’s explanation:Despite the pervasive desire to achieve high grades, students with the initial C or D, presumably because of a fondness for these letters, were slightly less successful at achieving their conscious academic goals than were students with other initials.

Notice that “slightly.” To find out how slight, you have to take a second look at the numbers on the axis of that gee-whiz graph. The Nelson-Simmons paper doesn’t give the actual means, but from the graph it looks as though the A students’ mean is not quite 3.37. The D students average between 3.34 and 3.35, closer to the latter. But even if the means were, respectively, 3.37 and 3.34, that’s a difference of a whopping 0.03 GPA points.

When you put the numbers on a GPA axis that goes from 0 to 4.0, the differences look like this.

According to Nelson and Simmons, the AB / CD difference was significant (F = 4.55, p < .001). But as I remind students, in the language of statistics, a significant difference is not the same as a meaningful difference.

According to Nelson and Simmons, the AB / CD difference was significant (F = 4.55, p < .001). But as I remind students, in the language of statistics, a significant difference is not the same as a meaningful difference.

Worlds in Collision

November 26, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

There’s been a lot written about how the Internet has shifted the boundary of private and public. People are willing to put more of their lives out there in cyberspace– most notably on networking sites like MySpace and Facebook – assuming, for some reason, that only their friends will have the ability or interest to stop and look.

But cyberlore teems with cautionary tales of the wrong people getting the wrong information. A prospective employer sees what a job candidate has put on his MySpace page and finds it much different from the picture the candidate presented in his resumé and interview. It’s the problem Goffman called “audience segregation.” We don’t present quite the same self to each group that we interact with – employers and drinking buddies, for example – and we do our best to make sure that the audiences for these different performances don’t overlap. Jeremy Freese closed down his blog because of this problem. (I can’t remember the specifics.)

It had all been academic for me till one night last week. My son was looking at Facebook, and looking over his shoulder I noticed that one of his “friends ” was a kid I’d known since they were in kindergarten together. I wanted to see a larger version of the postage-stamp size picture. No dice, Dad. He logged out.

So remembering that I had a Facebook account (though I never use it), I logged in on my laptop, and started looking through friends on my son’s page. My wife, too, was curious about these kids. My son, of course, was mortified. I couldn’t get to his actual page with his “wall” and other information. But I could scroll through the pages of his Facebook friends.

We both felt uncomfortable. He had always known that anyone in the world could view that list of friends, but he hadn’t really considered this possibility of his parents seeing it.

“This is not good,” he said. “Worlds are colliding.”

Posted by Jay Livingston

There’s been a lot written about how the Internet has shifted the boundary of private and public. People are willing to put more of their lives out there in cyberspace– most notably on networking sites like MySpace and Facebook – assuming, for some reason, that only their friends will have the ability or interest to stop and look.

But cyberlore teems with cautionary tales of the wrong people getting the wrong information. A prospective employer sees what a job candidate has put on his MySpace page and finds it much different from the picture the candidate presented in his resumé and interview. It’s the problem Goffman called “audience segregation.” We don’t present quite the same self to each group that we interact with – employers and drinking buddies, for example – and we do our best to make sure that the audiences for these different performances don’t overlap. Jeremy Freese closed down his blog because of this problem. (I can’t remember the specifics.)

It had all been academic for me till one night last week. My son was looking at Facebook, and looking over his shoulder I noticed that one of his “friends ” was a kid I’d known since they were in kindergarten together. I wanted to see a larger version of the postage-stamp size picture. No dice, Dad. He logged out.

So remembering that I had a Facebook account (though I never use it), I logged in on my laptop, and started looking through friends on my son’s page. My wife, too, was curious about these kids. My son, of course, was mortified. I couldn’t get to his actual page with his “wall” and other information. But I could scroll through the pages of his Facebook friends.

We both felt uncomfortable. He had always known that anyone in the world could view that list of friends, but he hadn’t really considered this possibility of his parents seeing it.

“This is not good,” he said. “Worlds are colliding.”

Execution and Deterrence

November 20, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

The Sunday New York Times had a front page article about recent studies showing that the death penalty deters murder. The studies, nearly all done by economists, give estimates of between 3 and 18 lives saved for each person executed.

The main critique of these studies argues that the small number of executions makes it impossible to draw solid conclusions. Last year, for example, Arizona had no executions; this year, Arizona executed one person. A change of 3 or even 18 murders in the next year, would probably fall within the range of random change.

In many areas of life, it makes sense to play the percentages. You send a left-handed batter against a right-handed pitcher. Even if the strategy doesn’t work this time, there’s no great consequence, and it will work in the long run thanks to the “law of large numbers” (what most people know as the “law of averages”). But , as the name says, that law is enforced only when the numbers are large. Do we want the numbers of executions to be that large?

Personally, when it comes to killing prisoners, I’d prefer a demonstration of deterrence that works with small numbers. I want to see a clearer link between cause and effect. Ideally, we would have evidence of at least three actual Arizonans (preferably 18) who were deterred by that execution. But of course we don’t have such evidence. All we have are estimates from complicated multiple regressions based on decades of data.

I don’t have the data sets or the statistical skills to do these regressions, so I did my own quick and dirty, highly nonscientific analysis of a couple of states – Texas and Oklahoma. In 1996, for example, the number of executions in Texas dropped from 19 to 3. The number of murders should have skyrocketed. But the next year, the number of murders decreased by 150 (from 1477 to 1327).

Then W. and Alberto got back to work, and in 1997, executions went from 3 to 37. Let’s see, at 10 saved lives per execution, murder in the next year should have been down by at least three hundred. But in fact, the next year, there were 20 more murders.

The numbers from Oklahoma, which started emulating its neighbor to the south, are similarly inconclusive. In 2000, it increased executions by 5 (from 6 to 11). Were there fifty or even fifteen fewer murders the next year? No, the number went from 182 to 185.

Yes, my method (or is it my methodolgy?) stinks. Its estimate of lag time is crude. It leaves out all those other factors that might affect murder rates, and it ignores the aggregate data. But when it comes to the state taking lives, I’m inclined to demand something that works every time, not just “in general.”

The economists’ formulations also leave out something important – a model of just how deterrence works. They simply make the standard economic assumption that raising the cost of something lowers demand. If you raise the cost of committing murder, fewer people will be willing to pay that price.

But before I accept the idea that deciding whether to kill someone is like deciding whether to buy a new car, I’d like to see some street-level evidence.

Finally, none of this speaks to other issues raised in the Times article and in the letters responding to it – the costs (especially relative to other anti-crime policies), the morality, and the risk of executing the innocent.

Posted by Jay Livingston

The Sunday New York Times had a front page article about recent studies showing that the death penalty deters murder. The studies, nearly all done by economists, give estimates of between 3 and 18 lives saved for each person executed.

The main critique of these studies argues that the small number of executions makes it impossible to draw solid conclusions. Last year, for example, Arizona had no executions; this year, Arizona executed one person. A change of 3 or even 18 murders in the next year, would probably fall within the range of random change.

In many areas of life, it makes sense to play the percentages. You send a left-handed batter against a right-handed pitcher. Even if the strategy doesn’t work this time, there’s no great consequence, and it will work in the long run thanks to the “law of large numbers” (what most people know as the “law of averages”). But , as the name says, that law is enforced only when the numbers are large. Do we want the numbers of executions to be that large?

Personally, when it comes to killing prisoners, I’d prefer a demonstration of deterrence that works with small numbers. I want to see a clearer link between cause and effect. Ideally, we would have evidence of at least three actual Arizonans (preferably 18) who were deterred by that execution. But of course we don’t have such evidence. All we have are estimates from complicated multiple regressions based on decades of data.

I don’t have the data sets or the statistical skills to do these regressions, so I did my own quick and dirty, highly nonscientific analysis of a couple of states – Texas and Oklahoma. In 1996, for example, the number of executions in Texas dropped from 19 to 3. The number of murders should have skyrocketed. But the next year, the number of murders decreased by 150 (from 1477 to 1327).

Then W. and Alberto got back to work, and in 1997, executions went from 3 to 37. Let’s see, at 10 saved lives per execution, murder in the next year should have been down by at least three hundred. But in fact, the next year, there were 20 more murders.

The numbers from Oklahoma, which started emulating its neighbor to the south, are similarly inconclusive. In 2000, it increased executions by 5 (from 6 to 11). Were there fifty or even fifteen fewer murders the next year? No, the number went from 182 to 185.

Yes, my method (or is it my methodolgy?) stinks. Its estimate of lag time is crude. It leaves out all those other factors that might affect murder rates, and it ignores the aggregate data. But when it comes to the state taking lives, I’m inclined to demand something that works every time, not just “in general.”

The economists’ formulations also leave out something important – a model of just how deterrence works. They simply make the standard economic assumption that raising the cost of something lowers demand. If you raise the cost of committing murder, fewer people will be willing to pay that price.

But before I accept the idea that deciding whether to kill someone is like deciding whether to buy a new car, I’d like to see some street-level evidence.

Finally, none of this speaks to other issues raised in the Times article and in the letters responding to it – the costs (especially relative to other anti-crime policies), the morality, and the risk of executing the innocent.

Buffett's Bet

November 18, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Often, a simple example is the best way to get a point across.

For example, the US tax system is incredibly complicated. To illustrate the idea that it also favors the wealthy, Warren Buffett (the second richest man in the country) has said that he pays a lower rate of income tax than does his secretary. Buffett’s income was about $47 million last year, and he paid about 18% in federal income taxes. His employees, whose incomes ranged from $60,000 to $750,000, paid an average of 33%.

It’s anecdotal evidence of course, so Buffett has extended it to the Forbes 400 – Forbes Magazine’s list of the 400 wealthiest Americans. He’s offered to bet any of them one million dollars that they paid a lower income tax rate than did their office secretaries and receptionists.

A few of them have responded, and Forbes online prints what they have to say.

These guys called Buffett names (senile, simplistic), but none of them took Buffett’s offer of the million-dollar bet.

John Catsimatidis ($2.1 billion) said, “The numbers can fool you . . . . I have a complex business . . . I own real estate, stocks and bonds, and so I have depreciation and write-offs.” Which is precisely Buffett’s point. The tax system favors rich people for the way they make their money, and it punishes people who work for a weekly paycheck.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Often, a simple example is the best way to get a point across.

For example, the US tax system is incredibly complicated. To illustrate the idea that it also favors the wealthy, Warren Buffett (the second richest man in the country) has said that he pays a lower rate of income tax than does his secretary. Buffett’s income was about $47 million last year, and he paid about 18% in federal income taxes. His employees, whose incomes ranged from $60,000 to $750,000, paid an average of 33%.

It’s anecdotal evidence of course, so Buffett has extended it to the Forbes 400 – Forbes Magazine’s list of the 400 wealthiest Americans. He’s offered to bet any of them one million dollars that they paid a lower income tax rate than did their office secretaries and receptionists.

A few of them have responded, and Forbes online prints what they have to say.

- Philip Ruffin ($2.1 billion) said that Buffett is “senile.”

- Kenneth Fisher ($1.8 billion) said, “He should stick to his area of expertise. It’s a little late to be trying to learn and teach social policy.”

- Randal J. Kirk ($1.6 billion) said, “His thesis here seems grossly simplistic.”

These guys called Buffett names (senile, simplistic), but none of them took Buffett’s offer of the million-dollar bet.

John Catsimatidis ($2.1 billion) said, “The numbers can fool you . . . . I have a complex business . . . I own real estate, stocks and bonds, and so I have depreciation and write-offs.” Which is precisely Buffett’s point. The tax system favors rich people for the way they make their money, and it punishes people who work for a weekly paycheck.

What Is That You're Drinking?

November 16, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Jeremy Freese says that after some time away from his rural Iowa roots, he started saying “soda” instead of “pop.” (Yes, he's blogging again. Jeremy’s retirement from blogging was analogous to Michael Jordan’s first retirement from basketball: unwanted by all but the retiree – and mercifully short. He’s now co-blogging at Scatterplot ).

But the soda/pop split is not so much rural-urban as it is regional

From these maps it looks as though the stores in Evanston and Chicago are about as likely to sell pop as soda. In Pittsburgh, where I grew up, it was “soda pop.” We didn’t want to take sides on such a controversial issue. And in Boston, when you go to the deli (oops, I mean the spa), you get a bottle of “tonic” (pronounced “taw-nic”).

The maps are from Bert Vaux’s dialect survey, and I find it fascinating. For instance, I had that thought that the use of “anymore” without a negative to mean “nowadays” was pure Pittsburgh (“ I do exclusively figurative paintings anymore”). True, only a small minority (5%) find it acceptable, but they are fairly well dispersed.

The maps are from Bert Vaux’s dialect survey, and I find it fascinating. For instance, I had that thought that the use of “anymore” without a negative to mean “nowadays” was pure Pittsburgh (“ I do exclusively figurative paintings anymore”). True, only a small minority (5%) find it acceptable, but they are fairly well dispersed.

Do you eat crawfish, crayfish, or crawdads? Do you have a yard sale, a garage sale, or a tag sale? Which word do you stress in “cream cheese” and which syllable in “pecan” (and is that “a” in “pecan” short or broad)?

“Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” Well, maybe. I can’t remember much about Brillat-Savarin’s personality assessment instrument. But “Tell me what you call what you eat, and I will tell you where you are.”

Posted by Jay Livingston

Jeremy Freese says that after some time away from his rural Iowa roots, he started saying “soda” instead of “pop.” (Yes, he's blogging again. Jeremy’s retirement from blogging was analogous to Michael Jordan’s first retirement from basketball: unwanted by all but the retiree – and mercifully short. He’s now co-blogging at Scatterplot ).

But the soda/pop split is not so much rural-urban as it is regional

From these maps it looks as though the stores in Evanston and Chicago are about as likely to sell pop as soda. In Pittsburgh, where I grew up, it was “soda pop.” We didn’t want to take sides on such a controversial issue. And in Boston, when you go to the deli (oops, I mean the spa), you get a bottle of “tonic” (pronounced “taw-nic”).

The maps are from Bert Vaux’s dialect survey, and I find it fascinating. For instance, I had that thought that the use of “anymore” without a negative to mean “nowadays” was pure Pittsburgh (“ I do exclusively figurative paintings anymore”). True, only a small minority (5%) find it acceptable, but they are fairly well dispersed.

The maps are from Bert Vaux’s dialect survey, and I find it fascinating. For instance, I had that thought that the use of “anymore” without a negative to mean “nowadays” was pure Pittsburgh (“ I do exclusively figurative paintings anymore”). True, only a small minority (5%) find it acceptable, but they are fairly well dispersed.Do you eat crawfish, crayfish, or crawdads? Do you have a yard sale, a garage sale, or a tag sale? Which word do you stress in “cream cheese” and which syllable in “pecan” (and is that “a” in “pecan” short or broad)?

“Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” Well, maybe. I can’t remember much about Brillat-Savarin’s personality assessment instrument. But “Tell me what you call what you eat, and I will tell you where you are.”

Norman Mailer

November 13, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

Norman Mailer died on Saturday. Sociologist/criminologist Chris Uggen posted briefly about Mailer’s criminal-justice-related writings – Chris is less impressed by Mailer’s fiction – so here’s my Mailer story. Not much, not sociology, not even lit crit, just one degree of separation.

In the summer of 1963, still in my teens, I was traveling across the country to San Francisco on a Greyhound bus. We’d stop every few hours in larger or smaller towns. You’d get off to use the bathroom or get a snack, and when you got back on, the demographics of the bus would have shifted. Different accents, different bodies.

We scaled the Rockies at night, crossed Utah as the sun was rising, and made it into Reno at mid-morning. The layover was an hour or so, and when I got back on the bus, my new seatmate was a gaunt, sallow, man in his thirties, much different from the plump and pasty folks I’d gotten used to over the previous thousand miles.

He’d stayed awake for thirty-six hours straight playing chuk-a-luck in a casino, winning a lot, losing it all back, and eventually developing a severe eye infection. He’d just gotten out of the hospital, and he was going to California to try to write for the movies and TV.

It was at about this point in our conversation that he pulled out a plastic bag with some odd food in it. It was thick crusty black bread covered with strange seeds and perhaps mold. “It’s Zen macrobiotic bread,” he said, and offered me a piece. I hadn’t heard of macrobiotics then, though I did know that Zen was cool. Still, I politely declined the offer.

He’d come from New York, where he’d taught English in grade school. But he also was an aspiring writer and hung out with the literary crowd in Greenwich Village. He’d been at parties with Norman Mailer.

He must have sensed my heightened interest at the mention of the name. Mailer was famous. He’d written a Big Novel, he’d published advertisements for himself, he’d invented the White Negro, he’d stabbed his wife.

“You know what another writer once told me at one of these parties?” he said. “‘Norman Mailer is a little Jewish kid from Brooklyn who still thinks it’s a big deal to get laid.’”

I remembered this pithy ad hominem when, a couple of years later, I read An American Dream. From that viewpoint, it seemed less a novel of political and social significance than a string of adolescent fantasies of sex and power. Like Chris Uggen, I never could never see the greatness of Mailer’s novels (at least the ones I read). But I remember being impressed immensely by Armies of the Night, even reading passages of it out loud to my roommates.

I remembered this pithy ad hominem when, a couple of years later, I read An American Dream. From that viewpoint, it seemed less a novel of political and social significance than a string of adolescent fantasies of sex and power. Like Chris Uggen, I never could never see the greatness of Mailer’s novels (at least the ones I read). But I remember being impressed immensely by Armies of the Night, even reading passages of it out loud to my roommates.

Posted by Jay Livingston

Norman Mailer died on Saturday. Sociologist/criminologist Chris Uggen posted briefly about Mailer’s criminal-justice-related writings – Chris is less impressed by Mailer’s fiction – so here’s my Mailer story. Not much, not sociology, not even lit crit, just one degree of separation.

In the summer of 1963, still in my teens, I was traveling across the country to San Francisco on a Greyhound bus. We’d stop every few hours in larger or smaller towns. You’d get off to use the bathroom or get a snack, and when you got back on, the demographics of the bus would have shifted. Different accents, different bodies.

We scaled the Rockies at night, crossed Utah as the sun was rising, and made it into Reno at mid-morning. The layover was an hour or so, and when I got back on the bus, my new seatmate was a gaunt, sallow, man in his thirties, much different from the plump and pasty folks I’d gotten used to over the previous thousand miles.

He’d stayed awake for thirty-six hours straight playing chuk-a-luck in a casino, winning a lot, losing it all back, and eventually developing a severe eye infection. He’d just gotten out of the hospital, and he was going to California to try to write for the movies and TV.

It was at about this point in our conversation that he pulled out a plastic bag with some odd food in it. It was thick crusty black bread covered with strange seeds and perhaps mold. “It’s Zen macrobiotic bread,” he said, and offered me a piece. I hadn’t heard of macrobiotics then, though I did know that Zen was cool. Still, I politely declined the offer.

He’d come from New York, where he’d taught English in grade school. But he also was an aspiring writer and hung out with the literary crowd in Greenwich Village. He’d been at parties with Norman Mailer.

He must have sensed my heightened interest at the mention of the name. Mailer was famous. He’d written a Big Novel, he’d published advertisements for himself, he’d invented the White Negro, he’d stabbed his wife.

“You know what another writer once told me at one of these parties?” he said. “‘Norman Mailer is a little Jewish kid from Brooklyn who still thinks it’s a big deal to get laid.’”

I remembered this pithy ad hominem when, a couple of years later, I read An American Dream. From that viewpoint, it seemed less a novel of political and social significance than a string of adolescent fantasies of sex and power. Like Chris Uggen, I never could never see the greatness of Mailer’s novels (at least the ones I read). But I remember being impressed immensely by Armies of the Night, even reading passages of it out loud to my roommates.

I remembered this pithy ad hominem when, a couple of years later, I read An American Dream. From that viewpoint, it seemed less a novel of political and social significance than a string of adolescent fantasies of sex and power. Like Chris Uggen, I never could never see the greatness of Mailer’s novels (at least the ones I read). But I remember being impressed immensely by Armies of the Night, even reading passages of it out loud to my roommates.

Labels:

Print

A Country of Have-Nots?

November 12, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

At a Republican fundraiser in 2000 where the minium buy-in was $800, George W. Bush referred to those in attendance as “the haves and the have-mores.”

Talk about “the haves and the have-nots” – the phrase Bush was alluding to – seemed old-fashioned at the time. To my ear, the terms sound like something out of the Depression. But the concept of haves and have-nots is making a comeback. The perception of inequality may be catching up to the reality.

In 1998, more than 70% of the US population rejected the idea that the country was divided between the haves and the have-nots. Today, as many people agree with that proposition as disagree (numbers are from the Gallup poll).

My first impulse is to trace it all to Bush– to see the shift as the chickens of false consciousness finally coming home to roost. After all, Bush did refer to the have-mores as “my base,” and his policies have rewarded them handsomely. But as the chart shows, the largest part of the change in perception was happening in the 1990s.

Along with their perception of an economically divided country, more Americans see themselves as being on the wrong side of the divide. (Numbers are from a recent Pew survey.)

In 1998, even among those in the lower third of the income distribution, 42% saw themselves as being among the “haves.” That percentage has since declined, of course, but so has the percentage of self-perceived “haves” in the middle and upper thirds of the distribution. That middle-group is especially interesting, with the percent thinking of themselves as among the “haves” declining from 61% to 43%.

In 1998, even among those in the lower third of the income distribution, 42% saw themselves as being among the “haves.” That percentage has since declined, of course, but so has the percentage of self-perceived “haves” in the middle and upper thirds of the distribution. That middle-group is especially interesting, with the percent thinking of themselves as among the “haves” declining from 61% to 43%.

Politically, this shift in perceptions would seem to work for the Democrats, who are more likely to be seen as the party for the have-nots. It’s certainly what John Edwards has been saying in his “two Americas” speeches. To counter the idea of a divided country, the Republicans seem to be relying on the unifying force of an external enemy. If we see ourselves as under attack from outside evildoers, terrorists, Islamofascists, et. al., we will have to rally together and ignore or deny internal divisions.

Posted by Jay Livingston

At a Republican fundraiser in 2000 where the minium buy-in was $800, George W. Bush referred to those in attendance as “the haves and the have-mores.”

Talk about “the haves and the have-nots” – the phrase Bush was alluding to – seemed old-fashioned at the time. To my ear, the terms sound like something out of the Depression. But the concept of haves and have-nots is making a comeback. The perception of inequality may be catching up to the reality.

In 1998, more than 70% of the US population rejected the idea that the country was divided between the haves and the have-nots. Today, as many people agree with that proposition as disagree (numbers are from the Gallup poll).

My first impulse is to trace it all to Bush– to see the shift as the chickens of false consciousness finally coming home to roost. After all, Bush did refer to the have-mores as “my base,” and his policies have rewarded them handsomely. But as the chart shows, the largest part of the change in perception was happening in the 1990s.

Along with their perception of an economically divided country, more Americans see themselves as being on the wrong side of the divide. (Numbers are from a recent Pew survey.)

In 1998, even among those in the lower third of the income distribution, 42% saw themselves as being among the “haves.” That percentage has since declined, of course, but so has the percentage of self-perceived “haves” in the middle and upper thirds of the distribution. That middle-group is especially interesting, with the percent thinking of themselves as among the “haves” declining from 61% to 43%.

In 1998, even among those in the lower third of the income distribution, 42% saw themselves as being among the “haves.” That percentage has since declined, of course, but so has the percentage of self-perceived “haves” in the middle and upper thirds of the distribution. That middle-group is especially interesting, with the percent thinking of themselves as among the “haves” declining from 61% to 43%.Politically, this shift in perceptions would seem to work for the Democrats, who are more likely to be seen as the party for the have-nots. It’s certainly what John Edwards has been saying in his “two Americas” speeches. To counter the idea of a divided country, the Republicans seem to be relying on the unifying force of an external enemy. If we see ourselves as under attack from outside evildoers, terrorists, Islamofascists, et. al., we will have to rally together and ignore or deny internal divisions.

A Fine and Public Place

November 8, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

We try to do right by the dead, to give them the best possible resting place. But what’s best? Apparently, Americans and French have very different ideas, as Polly’s pictures last week of a Paris cemetery reminded me.

I’m not much drawn to cemeteries, but Père Lachaise gets two stars in the Michelin Guide. It’s the final resting place of Chopin and Comte, Abelard and Heloise, Oscar Wilde, Modigiliani, Proust . . . . I was in Paris (this was many years ago) with some free time, so I went.

It didn’t look at all like a cemetery, at least not the cemeteries I had seen in the US. The one across from the University here seems typical.

The cemetery road curves gently through the lawns. Grass separates the headstones, with some space even between family members. The headstones are low, some even flat on the ground.

But at Père Lachaise, the lanes were narrower, with no grass to be seen. Instead of headstones, there were building-like structures tall enough that you might walk inside, crowded together with little or no space in between.

Sometimes, the structures were built right behind one another on a steep incline.

You could climb the steps and look down at the brick footpath below.

You could climb the steps and look down at the brick footpath below.

Nowhere to be found were the rolling lawns that I thought would be more appropriate for the eminent figures of a culture - Molière, Piaf, and the rest. Instead, what I was seeing was more like a scaled-down urban scene, the mausoleums resembling the stone apartment buildings of the city.

Then I realized : Our visions of the ideal life are reflected in the landscapes we provide for the dead. When Americans die, they go to the countryside. When the French die, they go to Paris.

Posted by Jay Livingston

We try to do right by the dead, to give them the best possible resting place. But what’s best? Apparently, Americans and French have very different ideas, as Polly’s pictures last week of a Paris cemetery reminded me.

I’m not much drawn to cemeteries, but Père Lachaise gets two stars in the Michelin Guide. It’s the final resting place of Chopin and Comte, Abelard and Heloise, Oscar Wilde, Modigiliani, Proust . . . . I was in Paris (this was many years ago) with some free time, so I went.

It didn’t look at all like a cemetery, at least not the cemeteries I had seen in the US. The one across from the University here seems typical.

The cemetery road curves gently through the lawns. Grass separates the headstones, with some space even between family members. The headstones are low, some even flat on the ground.

But at Père Lachaise, the lanes were narrower, with no grass to be seen. Instead of headstones, there were building-like structures tall enough that you might walk inside, crowded together with little or no space in between.

Sometimes, the structures were built right behind one another on a steep incline.

You could climb the steps and look down at the brick footpath below.

You could climb the steps and look down at the brick footpath below.

Nowhere to be found were the rolling lawns that I thought would be more appropriate for the eminent figures of a culture - Molière, Piaf, and the rest. Instead, what I was seeing was more like a scaled-down urban scene, the mausoleums resembling the stone apartment buildings of the city.

Then I realized : Our visions of the ideal life are reflected in the landscapes we provide for the dead. When Americans die, they go to the countryside. When the French die, they go to Paris.

Labels:

France

Let's Do the Time Warp Again

November 5, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

A piece on Facebook and advertising this morning on NPR’s Morning Edition quoted students at Berkeley as to what’s on their Facebook pages. The first voice was that of a girl (she sounded like she couldn't have been much older than first or second year) saying, “My favorite bands, like the Beatles and the Beach Boys . . . .”

Much to be said here regarding generations (could you have found a Berkeley student of the sixties who listed Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters among her faves?). But I’ll leave it at that.

And of course, you can still go to “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” (1975) and throw rice every Saturday midnight in Berkeley and many other cities around the world.

Posted by Jay Livingston

A piece on Facebook and advertising this morning on NPR’s Morning Edition quoted students at Berkeley as to what’s on their Facebook pages. The first voice was that of a girl (she sounded like she couldn't have been much older than first or second year) saying, “My favorite bands, like the Beatles and the Beach Boys . . . .”

Much to be said here regarding generations (could you have found a Berkeley student of the sixties who listed Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters among her faves?). But I’ll leave it at that.

And of course, you can still go to “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” (1975) and throw rice every Saturday midnight in Berkeley and many other cities around the world.

Faux Consciousness

November 2, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

“False consciousness.” It’s the escape valve in Marxian theory that explains why the workers, the exploited, the oppressed, so often act, vote, and think against their own interests. They fail to see the reality of the system that exploits them. The Marxists try to enlighten the workers as to that realty, but too often, the Marxists’s target audience seems to be tuned into the Fox network. (Or is that the Faux network?)

Many years ago, I was riding the bus to work with my colleague Peter Freund. As we passed a Chicken Delight, he pointed out the window to its large iconic sign. “The perfect representation of false consciousness,” he said.

I haven’t seen that type of sign for a while, but I was reminded of it when I saw this French version of fausse conscience, posted by Polly in her expat blog.

“Members of a subordinate class (workers, peasants, serfs) suffer from false consciousness in that their mental representations of the social relations around them systematically conceal or obscure the realities of subordination, exploitation, and domination those relations embody.” (Daniel Little)

The chicken happily serving itself up on a platter to be devoured by its exploiters.

Posted by Jay Livingston

“False consciousness.” It’s the escape valve in Marxian theory that explains why the workers, the exploited, the oppressed, so often act, vote, and think against their own interests. They fail to see the reality of the system that exploits them. The Marxists try to enlighten the workers as to that realty, but too often, the Marxists’s target audience seems to be tuned into the Fox network. (Or is that the Faux network?)

Many years ago, I was riding the bus to work with my colleague Peter Freund. As we passed a Chicken Delight, he pointed out the window to its large iconic sign. “The perfect representation of false consciousness,” he said.

I haven’t seen that type of sign for a while, but I was reminded of it when I saw this French version of fausse conscience, posted by Polly in her expat blog.

“Members of a subordinate class (workers, peasants, serfs) suffer from false consciousness in that their mental representations of the social relations around them systematically conceal or obscure the realities of subordination, exploitation, and domination those relations embody.” (Daniel Little)

The chicken happily serving itself up on a platter to be devoured by its exploiters.

Better Off?

October 31, 2007

Posted by Jay Livingston

“Are you better off than you were four years ago?” asked Ronald Reagan of Americans in a televised presidential debate with Jimmy Carter in 1980. Many people think that this question helped win the election for Reagan. That was then.

What about now? Back in August, I cited a New York Times article by David Cay Johnston showing that average income in 2005 was still lower than it had been in 2000. But I wondered why Johnston hadn’t used median income rather than the mean since the mean is so distorted by changes among the very rich.

Mr. Johnston has e-mailed an elbow in the ribs calling my attention to a Times article he wrote two weeks ago showing income changes for different income groups. I confess I hadn’t seen it (nor had any of the economist blogs I look at made mention of it.).

The message is basically the same. For all but the top 5%, incomes were still slightly lower in 2005 than they had been in 2000. But that’s not quite the whole story. The graph in the article shows both pre-tax and post-tax income.