May 19, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

“Dr. Oz should declare victory. It makes it much harder for them to cheat with the ballots they ‘just happened to find.’” So posted Donald Trump on his social media platform Truth Social.*

He may be right. By declaring victory, you make that the default outcome. You put the burden of proof on the other side. That was Trump’s strategy in 2020. He started claiming victory before the election. Thus, his claims of victory after the election were merely a continuation of an established “fact,” even though that fact was established only by Trump’s repeatedly asserting it. That made it easier for his supporters to remain convinced that he won and to believe all his claims about fraudulent vote counts. It also apparently has raised doubts even among those who were not ardent Trump supporters.

In the pre-Trump era, a candidate in Dr. Oz’s position would say something like, “Well, it’s a very close, and we’ll have to wait for all the absentee ballots. But when all the votes are counted, I’m sure that we will have won.” That is in fact the situation that exists.

Or he could play the Trump card and declare victory – loudly and frequently, on TV and on Twitter. If the final tally shows McCormick winning, that result will seem to go against an established fact. And even if courts and recounts uphold the result, Dr. Oz will avoid being labeled a loser.

Maybe this same strategy would work in other areas. I imagine Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks, declaring on Tuesday that a Mavericks victory the next night was certain. Then, after the game, which Golden State won 112-87, he could claim that there was basket fraud – that many of the Warriors’ points were “fake baskets.” He could get Dinesh D’Souza to make a film showing nothing but Mavericks’ baskets and the Warriors’ misses. He could call up the scorekeeper and tell him to “find me just 26 more points.”

OK, maybe we’re not there yet in basketball. But in politics this is another area where Donald Trump may have a lasting influence. I expect that more politicians will use the strategy of declaring victory and then claiming voter fraud. The gracious concession speech will become a rare event.

----------------------

* I think that they call these posts “truths.” Twitter has Tweets; Truth Social has Truths. I don’t think they have yet come up with a verb equivalent to Tweeting. “Dr. Oz should declare victory,” Donald Trump truthed?

A blog by Jay Livingston -- what I've been thinking, reading, seeing, or doing. Although I am a member of the Montclair State University department of sociology, this blog has no official connection to Montclair State University. “Montclair State University does not endorse the views or opinions expressed therein. The content provided is that of the author and does not express the view of Montclair State University.”

Making “I Won” the Default

“Julia” — Serving Up Words Before Their Time

May 4, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

“The Marvelous Mrs. Anachronism” (here) is the post in this blog with by far the most hits and comments. And now we have “Julia,” the HBO series about Julia Child and the creation of her TV show “The French Chef.” It’s set in roughly the same time period, the early 1960s. And like “Mrs. Maisel,” it offers a rich tasting menu of anachronisms.

I don’t know why the producers don’t bother to check their scripts with someone who was around in 1962 – a retired sociologist, say, who is sensitive to language – but they don’t. Had they done so, they would have avoided the linguistic equivalent of a digital microwave in the kitchen and a Prius in the driveway. They would not have had a character say, “I’m o.k. with it.” Nor would an assistant assigned a task say, “I’m on it.” Nobody working with Julia would be excited to be on the front lines of “your process.” “Your method” perhaps or “your approach” or even “all that you do,” but not “your process.”

If you’re a TV writer, even an older writer of fifty or so, these phrases have been around for as long as you can remember, so maybe you assume they’ve always been part of the language.

But they haven’t. Sixty years ago, people might have asked how some enterprise made money or at least made ends meet. But they would not have asked it the way Julia’s father asks her: “What's the business model down there? Does public television even* have a business model?”

In her equally anachronistic reply, Julia says, “Nothing's a done deal yet,” That one too sounded wrong. I don’t recall any done deals in 1962.

To check my memory, I went to Google nGrams. It shows the frequency of words and phrases as they occur in books. Most of the phrases that seemed off to my ear did not appear in books until the 1980s. A corpus of the language as spoken would have been better, and there’s a lag of a few years before new usages on the street make it to the printed page. But that lag time is certainly not the twenty years that nGrams finds.

In another episode, we hear “cut to the chase,” but it was not till the 80s that we skipped over less important details by cutting to the chase. (Oh well, at least nobody on “Julia” abbreviated a narrative with “yada yada.”) Or again, a producer considering the possibilities of selling the show to other stations says, “This could be game changer.” But “game changer” didn’t show up in books until four decades after “The French Chef” went on the air.

“This little plot is genius,” says Julia’s husband. It may have been, but in 1962, genius was not an adjective. An unusual solution to a problem might be ingenious, but it was not simply “genius.” Even more incongruous was Julia’s telling the crowd that shows up for a book signing in San Francisco, “I'm absolutely gobsmacked by this turnout.” Gobsmacked originated in Britain, but even in her years abroad, Julia would not have heard the term. Brits weren’t gobsmacked until the late 1970s, with Americans joining the chorus a decade or so later.

I heard other dubious terms that I did not know how to check. “The Yankees are toast,” says one character, presumably a Red Sox fan. It’s not just that in 1962 the Yankees were anything but toast, winning the AL pennant and the World Series; I doubt that anyone was “toast” sixty years ago.

The one that bothered me most was what Julia’s friend Avis says after making a small play on words. She adds, “See what I did?” I’m pretty sure this is a very recent usage and was not around in 1962. I’d just as soon not have it around today.

Finally, in the latest episode, which I just now saw and which inspired me to write this post, we have the anachronism that nobody notices — “need to” instead of “should” or “ought to” or other words that carry a hint of what is right or even moral. In “Julia,” a young couple meet for lunch at a diner. It’s a blind date, and as they talk, it becomes clear that they are a good match. They talk some more, and we cut to a different plot line. When we come back to the diner, the couple are still there, still talking, but they are now the only ones left in the place. The waitress comes to the table and tells them patiently, “You need to go.”

What she means of course is that she needs for them to go. In 1962, she would not have phrased it in terms of their needs. She would have said, “You have to go.”

-------------------------------

* “Even” as an intensifier in this way may also not have come into use until much later in the century. See this Language Log post on “What does that even mean?”

Robert Morse, 1931 - 2022

April 21, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

The opening sentence of the Times obit for Robert Morse mentions his roles in both “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” in 1961 and “Mad Men” forty-six years later. Those Morse roles were linked in subtler ways — the characters’ career trajectories and their clothing choices, as. I pointed out in a 2010 post which I am hauling out of the archives on this Throwback Thursday.

The post was mostly about America’s concern with “conformity,” but Morse’s performance in the video from “How to Succeed” is worth two minutes and fifty-three seconds of your time even if you’re not considering the cultural-historic questions.

*******************

July 1, 2010Posted by Jay Livingston

“How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” was on TMC Tuesday night in honor of the centenary of Frank Loesser’s birth. The Broadway show opened in 1961, sort of a musical comedy version of William H. Whyte’s 1956 best-seller The Organization Man.

Loesser’s musical was light satire; Whyte’s book was sociology. But the message of both was that corporations were places that demanded nearly mindless conformity of all employees. Or as Mr. Twimble tells the ambitious newcomer (J. Pierpont Finch), “play it the company way.”

FINCH:When they want brilliant thinking / From employeesConformity was a topic of much concern in America in those days, in the popular media and in social science (as in the Asch line length experiments). Today, not so much.

TWIMBLE: That is no concern of mine.

FINCH: Suppose a man of genius / Makes suggestions.

TWIMBLE: Watch that genius get suggested to resign.

the Organization Man, if he ever existed, is dead now. The well-rounded fellow who gets along with pretty much everyone and isn’t overly brilliant at anything sees his status trading near an all-time low. And all those brilliant screwballs whose fate Whyte bemoaned are sitting now on top of corporate America.

That’s one version. I don’t really know if the corporate climate is different today (where’s an OrgTheorist when you need one?). No doubt, “brilliant screwballs” can find save haven in corporations, at least in areas that require technical brilliance, and some may wind up at the top. But I wonder how such quirkiness survives in other areas like sales. Barbara Ehrenreich, in her recent book Bright-Sided, looks at corporations today – with their motivational speakers and “coaches” – and sees the same old demand for cheerful, optimistic obedience, especially in this era of outsourcing and downsizing.

The most popular technique for motivating the survivors of downsizing was “team building” – an effort so massive that it has spawned a “team-building industry” overlapping the motivation industry. . . .Or as Frank Loesser put it,

The literature and coaches emphasize that a good “team player” is by definition a “positive person.” He or she smiles frequently, does not complain, is not overly critical, and gracefully submits to whatever the boss demands.

FINCH: Your face is a company face.Here’s the whole song from the 1967 film version:

TWIMBLE: It smiles at executives then goes back in place.

The movie has another uncanny resemblance to today. The costumes and even the sets look like “Mad Men” – not surprising since both are set in the New York corporate world of the early 1960s. But there’s more. In the Broadway show and then the musical of “How to Succeed,” Robert Morse (Finch), rises to become head of advertising. Fifty years later, in “Mad Men,” Robert Morse (Bert Cooper) is the head of an advertising agency. (And he’s still wearing a bow tie.)

Baby Names and the Value on Distinctiveness

March 15, 2022

Posted by Jay Livingston

Namerology, the former Baby Name Voyager (here),is a great resource for anyone interested in graphs showing trends in baby names in the US. It uses the data from the Social Security Administration, but it’s graphs are much better than those you can create on the SSA Website. For instance, it allows you to compare names.

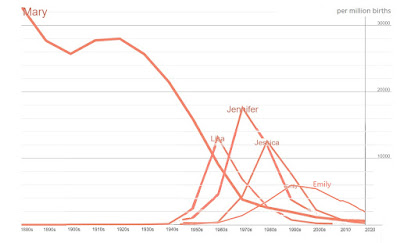

I wanted to explore the idea that the diversity of names is increasing. The most popular names today are not nearly as dominant as popular names in the past. It’s like TV shows. The ratings or share-of-audience of today’s most popular shows are numbers that twenty years ago would have marked them for cancellation. Compare the most popular name for girls born in the 1990s, Emily, with her counterpart in the 70s, Jennifer.

Jennifer’s peak was three times higher than Emily’s.

Jennifer also stacks up well against the top name of the sixties (Lisa) and of the eighties (Jessica).

Jennifer’s popularity was extraordinary. Jessica was at the top for nine of the eleven years from 1985 to 1995. And Lisa held top spot for eight years, 1962 - 1969. But Jennifer was number one for fifteen years, 1970-1984. We will probably never see her like again.

But then along comes Mary. The numbers for Mary back in the day dwarf those for Jennifer at the height of her popularity.

I read this graph to mean that the way we think about names has changed. Today, we just assume that you don’t want to give your kid the same name that everyone else has. You want something that different, but not too different. But a hundred years ago, distinctiveness was not important criterion for parents choosing a name. Year in year out, the girls name most often chosen was the same year in year out — Mary.

Names may be only part of a more general change in ides about children. Demographer Philip Cohen (here) speculates that compared with parents in the early 1900s, parents in the latter half of the twentieth-century saw each child as a unique individual. After all, children were becoming scarcer. From 1880 to 1940, the average number of children per family declined from 4.2 to 2.2, And while Mary remained the most popular name throughout that period, its market share declined from over 30,000 per million to about 20,000 per million.

The real shift starts in the 1960s. It may have been part of the general rejection of old cultural ways. But this was also the end of the baby boom. With new birth-control (the pill), having children became more a matter of choice. Family size declined even further. Each child was special and was deserving of a special name.