September 30, 2006

Posted by Jay Livingston

Posted by Jay Livingston

You can’t copyright a joke, you can’t copyright a magic trick. So what do you when another performer steals your stuff?

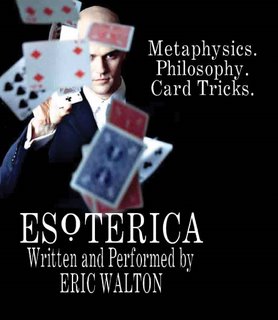

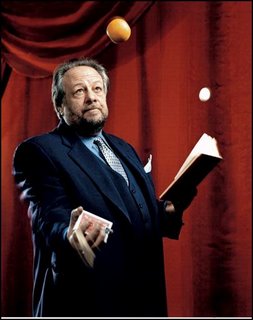

Eric Walton is a magician. He’s doing a show, “Esoterica,” at a theater down on E. 15th. But some of his act resembles a show another magician, Ricky Jay [photo on the right], did a few years back. The Times ran a story (here) on the on the controversy.

Jules Fisher, the Tony Award-winning lighting designer, who is also an amateur magician . . . .sent an e-mail message to Mr. Walton saying the presentation of the Knight's Tour “so closely approaches its inspiration as to border on plagiarism.”This was of some interest to me because many years ago, I was hanging around with magicians, thinking that there might be something interesting and sociological there. In survey research, you start with an idea, then you get data to support it. But I was doing ethnographic research, where you often begin with the “data,” usually a group of people in some setting, not sure exactly what you’re looking for but with the sense that, as I once heard William H. Whyte say, “If I look at something long enough, eventually I’ll see something nobody else has seen.”

“Does performing an existing effect, or variation thereof, confer upon the performer of it ownership of that effect, or the exclusive and perpetual right to all subsequent interpretations of it?” Mr. Walton asked in his message. “On this point you and I are obviously in disagreement.”

I wasn’t as successful as Whyte. I never did figure out a framework for my observations with the magicians. I don’t even know where my fieldnotes are now. But on the topic of plagiarism, I do remember this: When magicians talk among themselves, when they demonstrate tricks for one another, they are unusually scrupulous about giving credit where it’s due. Much like academics, they footnote everything. They’ll say things like, “The routine combines Gene Finnell’s Free Cut Principle with the plot from Dai Vernon’s Aces.” They are especially careful to footnote the specific “moves” (sleights) that they use in a trick. “This is an extension of a coin change by Dr. E. Roberts in Bobo,” (Bobo being the author of a classic book on coin magic.)

The problem is that you can’t do this kind of footnoting in a performance. In the first place, it comes close to disclosing secrets of how the trick is done. But more important, the audience doesn’t care. They want to be entertained, not informed. What’s important to magicians — authorship, originality— is not important to the audience. I remember once seeing a street magician in New York who had taken most of his act from another street magician I’d seen a couple of years earlier but who had since moved on. He finished his little seven-minute show and passed the hat for donations from the small sidewalk crowd. The crowd was pleased. I was not really a magician but I was in the know, and I resented his stealing the other guy’s act. I had the feeling that real magicians would too. As the crowd dispersed and the magician turned back to arrange his props for the next show, I approached him and mentioned something about the other magician. “Oh yeah,” he exclaimed, “he’s my idol. I’ve patterned my whole act after his.” And for some reason, I felt that made it okay. I think other magicians hearing this would have had the same reaction. They might not have admired him; they might have looked down on his lack of originality. But his footnoting would have legitimized his act.

Eric Walton cannot get up on stage and say, “A lot of what I’m going to do tonight I took from Ricky Jay.” I suppose he could mention Jay in the notes in the Playbill. And he did, in a way. It turns out that Eric Walton had given an interview to a website where he said that Ricky Jay had been a source of inspiration to him. However, after others noted the similarity of the shows, Walton asked the website to remove that quote.

If students plagiariaze papers, they can be given an F for the paper or even the course. They can even be tossed out of school. If writers plagiarize, they can be sued for real money. But if a performer steals someone else’s act, he is subject only to informal social control

No comments:

Post a Comment